Johann Reichhart was born on April 29, 1893 in Wichenbach near Wörth an der Donau into a family of executioners going back eight generations. During World War I, he served in the trenches at Verdun. On March 23, 1924, Reichhart applied to the Bavarian State Ministry of Justice in Munich for the position of executioner. The administration accepted his offer, allocated 150 Goldmark for each execution he performed and announced, “From April 1, 1924, Reichhart takes over the execution of all death sentences coming in the Free State of Bavaria to the execution by beheading with the guillotine.” His career began on July 4, 1924 – when he beheaded two men on the guillotine at Landshut – spanned the time of the Weimar Republic and the Third Reich.

In 1929, however, his reputation was such that he fled Germany to Holland, opening a vegetable market in The Hague. During these years, he returned to Bavaria only when he received an encrypted telegram informing him of an assigned execution. With Hitler’s rise to power in 1933, Reichhart returned to Germany and joined the Nazi Party four years later. The Nazis proved prolific superiors and Reichhart made so much money as an executioner that in 1942 he bought a private home in the Gleisse Valley, near Deisenhofen, south of Munich. Reichhart executed 3,165 people, most of them during the period 1939 – 1945 when, according to his own records, he put 2,876 men and women to death. In this Third Reich era, the executions derived largely from heavy sentences handed down by the Volksgerichtshof (People’s Court) for political crimes such as treason, and included Sophie and Hans Scholl of the German resistance movement White Rose (Reichhart executed them at Munich’s Stadelheim Prison.) Most of these sentences were carried out by Fallbeil (“drop hatchet”), a shorter, largely metal re-designed German version of the French guillotine. Reichhart served as one of four principal executioners in the Third Reich.

Reichhart was very strict in his execution protocol, wearing the traditional German executioners’ attire of black coat, white shirt and gloves, black bow tie and top hat. He initially served as the Bavarian State Executioner. His work took him to many parts of occupied Europe, including Poland and Austria. He claimed during questioning that, toward the end of the war, as the allied armies closed in, he supposedly disposed of his mobile guillotine in a river, a claim that seems to be related to almost every guillotine in Germany at the end of the conflict.

Following Victory in Europe Day in 1945, Reichhart, who was a member of the Nazi Party, was arrested for the purposes of denazification, but was not immediately tried for carrying out his duty as one of the primary judicial executioners in the Third Reich. He was subsequently employed by the Occupation Authorities beginning in November 1945, to help execute Nazi war criminals at Landsberg am Lech by hanging. He appears to have worked for the Americans only through May 1946. According to a reliable source, Reichhart spoke to the prison commandant, sometime after hanging seven men on May 29, stating that he was worried that he was executing some innocent men. He stated that, although he was afraid of repercussions, he would rather face judicial proceedings than continue as the hangman. One source states that one of his sons assisted him at Landsberg in the executions; photographic records can not confirm that. One source credits Reichhart with hanging 42 German war criminals after the war, but it is far more likely that he hanged only 21 condemned men at Landsberg Prison and was not involved in any way with the Nürnberg executions.

His work at Landsberg terminated, police arrested Reichhart at his home in May 1947 and took him to an internment camp at Moosburg an der Isar. His court proceedings began on December 13, 1948 at Munich. On November 29, 1949, in a German (probably Bavarian) tribunal, Reichhart was sentenced to strict punishment measures. The court sentenced him to two years confinement in a labor camp and confiscation of 50% of his assets. He was forbidden from ever holding public office, voting or the right to engage in politics. Finally, Reichhart was forbidden to own a motor vehicle or possess a driver’s license. He also was ordered to pay 26,000 marks for the cost of the trial.

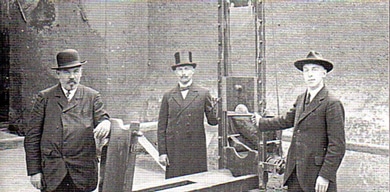

Johann Reichhart adjusting rope prior to hanging Martin Weiss, former commandant of Dachau and Neuengamme concentration camps.

Financially ruined, his marriage failed, and one son, Hans, committed suicide in 1950 (he was 23.) In 1963, there were public demands, during a series of taxi driver murders, for the re-introduction of the death penalty in West Germany and Reichhart was vocal in his support for this legislation. He maintained that the preferred method of killing should be the guillotine, as it was the fastest and cleanest method of execution.

Johann Reichhart died in in a nursing home at Dorfen near Erding, Bavaria, on April 26, 1972. On May 2, 1972, his body was cremated at the crematorium at the Ostfriedhof in Munich. He is buried in in the Ostfriedhof in a family grave (Section 47, Row 2, #21) that also contains his two sons and his uncle, Franz Xavier, a prolific executioner in his own right.