Stalingrad

The Death of the German Sixth Army on the Volga, 1942-1943

Stalingrad! The turning point for World War II in Europe. The perfect storm that would lead to the death of an army – the German Sixth Army. Not a quick kill by the Soviets, it bled out Germany’s biggest and best army level formation, over five months, and sent Germany’s allies, Italy, Romania and Hungary reeling on the East Front. This is a day-by-day account of that fight, which is so detailed it needed two volumes!

Led by Adolf Hitler, who insisted that his forces fight to the last man and bullet, the Sixth Army became enticed by an objective that continued to be just past their grasp. Believing that Stalingrad would be theirs “if only” one more attack against the urban rubble was mounted, the Sixth Army did not see that it was in a situation where if something did go wrong, it would not “see” impending doom until it was too late.

That something was the massive Soviet attack that broke through both flanks of the Sixth Army in such a violent manner and to such a great operational depth that any hope of relieving the surrounded pocket from the outside in such horrible winter conditions was illusionary.

Thus, defeat was in order for the Sixth Army, but it would not end there. Adolf Hitler had insisted that this would be a fight between the supermen of Aryan Germany against the sub-humans of Slavic Russia. In this fight, according to Nazi ideology, the sub-humans had no right to live. Given the polar ideological differences of Fascism and Communism, combined with this racial antagonism, when the Red Army did gain the upper hand and isolate the German forces around Stalingrad in November 1942, the situation guaranteed that the Sixth Army would not only be defeated, but that it and most of its soldiers were headed for annihilation.

It would be a bloody fight all around. In the whole of the Stalingrad Campaign, the Red Army suffered 1,100,000 casualties – a full 485,751 were killed in action or those who shortly afterward died of their wounds. These bloody losses, combined with the massive casualties experienced by the Germans, led to Stalingrad assuming a strategic importance that would ensure that the loser of the battle would have its national will seriously questioned.

The format of the study is that of a day-by-day presentation. Light data (moon, sunrise and sunset) and weather data are presented first. The various subordinate corps are listed in numerical order, with the divisions listed under each corps. The German Army frequently changed task organization, so the reader should not note with alarm that a division is assigned to one corps on one day, a second corps for the next couple of days and even a third corps within the same week. The study has attempted to describe what each division was doing, where it was located and how many losses it suffered for the day.

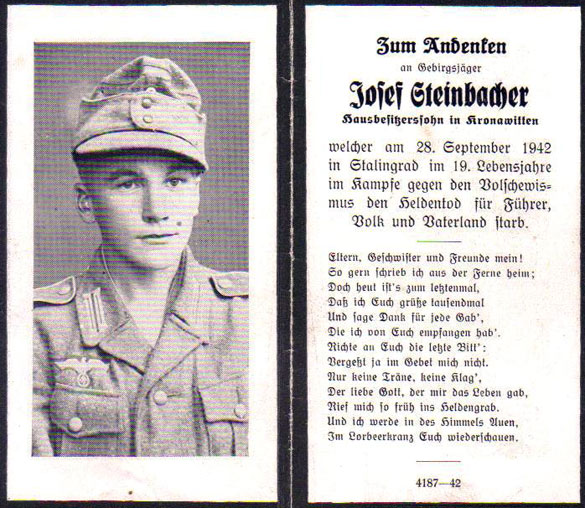

Left at this point, this study might have been too antiseptic; valuable for hard-core Stalingrad researchers, but not interesting enough for other readers. To present a human-interest side, I decided to include, for as many days possible, a death card (Sterbebild) for a soldier who died in the Sixth Army during the Stalingrad campaign. Josef Stalin, for whom the city was named, reportedly said during the war, “The death of one man is a tragedy; the death of millions is a statistic.” While the exact origin of the quotation has been called into serious doubt, its validity remains true; reading the personal details of each of the soldiers listed on the death cards drives home the point that the death of the Sixth Army was a crushing blow throughout Germany.

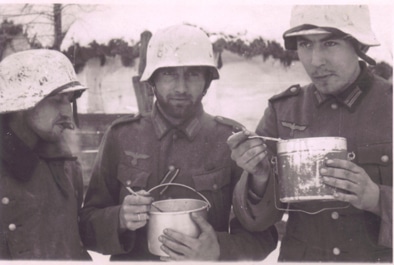

The study also includes letters home from soldiers in the 71st Infantry Division, 79th Infantry Division, 94th Infantry Division, 100th Jäger Division and 371st Infantry Division. This cross-section of the Sixth Army reflects how the individual soldier survived in the midst of lice, poor rations, an implacable enemy and a hopelessly cold winter.

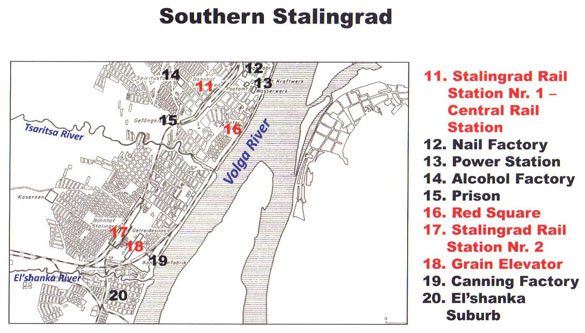

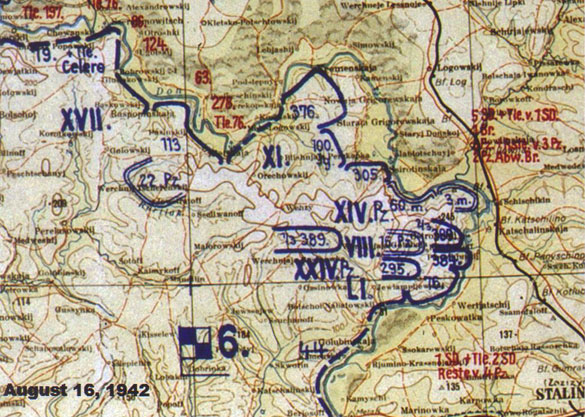

While the end date of the campaign – February 2, 1943 – is obvious, a start date proved more elusive to determine. Several could have been selected. “Case Blue,” the attack east toward Stalingrad and the Caucasus, began June 28, 1942. August 23, 1942 marked the date that the 16th Panzer Division of the Sixth Army dashed to the Volga River just north of Stalingrad; either date could have been logical. This study selected August 15, 1942 – the date that Sixth Army units reached the portion of the Don River north of Kalach. This segment of the Don River was the final natural barrier west of the Stalingrad. Breaching that, it was only a matter of time until German forces reached the Volga.

What they did after they reached the river was a different story. To the Sixth Army, it was one more river to conquer. What Paulus and his generals did not realize was that the Volga River was horribly mis-named. As events would prove, a more-appropriate moniker would have been “Phlegethon” – the name of the river of blood that boils men’s souls, found in the Seventh Circle of Hell in Dante’s Inferno.

307 photographs, over 150 maps. Stalingrad: The Death of the German Sixth Army on the Volga, 1942-1943 two-volume set, $69.99!

Volume 1 – The Bloody Fall

Volume 2 – The Brutal Winter

Comments on Stalingrad

“If I were writing about the Battle of Stalingrad, fiction or non-fiction, your book would be on my desk throughout the entire project. It would probably be dog-eared by the completion of the work!”

– John Calvin Webmaster, WWII Aerial Photos and Maps

“It is not often a book comes along that sweeps me off my feet, but one recently arrived on my desk…As a Stalingrad writer, I’m disappointed that it wasn’t me who created this book – but as a Stalingrad reader, I’m absolutely thrilled…Your book set will save me a lot of time…now, you’ve done all the hard work for me.”

– Jason Mark author of Island of Fire: The Battle for the Barrikady Gun Factory in Stalingrad November 1942-February 1943 and Death of the Leaping Horseman, 24. Panzer-Division in Stalingrad

“It is monumental, and it will be an excellent companion for my trilogy…In addition to providing the German detail I could not, the two volumes are both encyclopedic and readable.”

– Colonel David M. Glantz, US Army Retired author of To the Gates of Stalingrad: Soviet-German Combat Operations, April-August 1942 and Armageddon in Stalingrad: September-November 1942 (The Stalingrad Trilogy, Volume 2)

Stalingrad Excerpt 1

September 28, 1942

Weather: sunny, bright, changing temperatures, 81° F

Sunrise: 5:56 a.m.; Sunset: 5:49 p.m.

Moon: Waning Gibbous; 84% illumination

Sixth Army – Bombers and dive-bombers from the Luftwaffe‘s VIII Air Corps pounded Stalingrad in large-scale attacks, concentrating on Volga shipping and the Volga west bank. The army headquarters was located at Golubinskaya.

VIII Corps – The aim of the corps was to prepare to exchange defensive sectors of the divisions. The 754th Pioneer Battalion was assigned to the corps. The corps suffered the following officer casualties: two killed in action; eight wounded in action.

76th Infantry Division – The division defended in sector southwest of Samofalovka and north of Borodkin, against the 260th Rifle Division and 173rd Rifle Division. To the northwest was the 305th Infantry Division; to the east was the 60th Infantry Division (Motorized.) Enemy attacks were supported by heavy mortar and artillery fire, but were repelled. The division reported that of its nine infantry battalions, two were average and seven were weak in combat power; the division rated its combat engineer battalion as average. The division lost eight NCOs/enlisted killed in action; four officers and 30 NCOs/enlisted were wounded in action.

305th Infantry Division – The division defended in sector from the Don River, north of Nizhne-Gnilovskii, to west of Kotluban’, against the 298th Rifle Division. To the east was the 76th Infantry Division; to the north was the 384th Infantry Division. The division reported that of its nine infantry battalions, three were strong, three were medium-strong and three were average in combat power; the division rated its combat engineer battalion as strong. The division lost two NCOs/enlisted killed in action; one officer and 11 NCOs/enlisted were wounded in action.

XI Corps – The corps suffered the following officer casualties: four wounded in action.

44th Infantry Division – The division defended in sector Kurchajessowskij-Kamyshinskiy-Hill 171.0-Hill 180.9-Sirotinskaya-Khmelevskoy, against the 343rd Rifle Division. The division headquarters was located at Verkhne-Golubaja. To the west was the 376th Infantry Division; to the east was the 384th Infantry Division. The division reported that of its nine infantry battalions, five were strong, three were medium-strong and one was weak in combat power; the division rated its combat engineer battalion as strong. The division lost two NCOs/enlisted killed in action; ten NCOs/enlisted were wounded in action.

376th Infantry Division – The division defended in sector near Blizhniaia-Perekopka, against the 23rd Rifle Division. To the west was the 1st Romanian Cavalry Division; to the east was the 44th Infantry Division. The division reported that of its seven infantry battalions, four were average and three were weak in combat power; the division rated its combat engineer battalion as weak. The division lost six NCOs/enlisted killed in action; 21 NCOs/enlisted were wounded in action; 15 men were reported missing in action.

384th Infantry Division – The division defended in sector west of the Don River near Trekhostrovskaia to Podgorskii, against attacks by the 27th Guards Rifle Division but gave up terrain near the river to almost Hill 245. To the west was the 44th Infantry Division; to the south was the 305th Infantry Division. The division reported that of its six infantry battalions, three were average and three were weak in combat power; the division rated its combat engineer battalion as weak. The division lost five NCOs/enlisted killed in action; one officer and 15 NCOs/enlisted were wounded in action.

XIV Panzer Corps – The corps suffered the following officer casualties: three killed in action; seven wounded in action.

3rd Infantry Division (Motorized) – The division defended in sector, from the Tartar Hill-Hill 111.1-Hill 129.6-Hill 131.2, against the 299th Rifle Division, the 38th Guards Rifle Division, the 116th Rifle Division and the 343rd Rifle Division. To the east was the 16th Panzer Division; to the west was the 60th Infantry Division (Motorized.) The division reported that of its five motorized infantry battalions, all four were average in combat power; the division rated its combat engineer battalion as average.

16th Panzer Division – The division defended in sector, from Hill 139.7 to the Volga and from the Volga southwest to Hill 145.1, north of Orlovka, against the 120th Rifle Division, the 84th Rifle Division and the 64th Rifle Division. Along its southern front, the division defended to contain enemy forces at Orlovka. To the west was the 3rd Infantry Division (Motorized); to the southwest was Battle Group Stahel. The division reported that of its five Panzer grenadier battalions, three were medium-strong and two were average in combat power; the division rated its combat engineer battalion as average.

60th Infantry Division (Motorized) – The division defended in sector, from south of Kotluban’ Station near Borodkin to Kuz’michi against the 41st Guards Rifle Division, the 49th Rifle Division, the 231st Rifle Division, the 233rd Rifle Division, the 39th Guards Rifle Division, the 316th Rifle Division and the 207th Rifle Division. Along its southern front, the division defended to contain enemy forces at Orlovka. To the west was the 76th Infantry Division; to the east was the 3rd Infantry Division (Motorized.) The division reported that of its seven motorized infantry battalions, four were average, two were weak and one was exhausted in combat power; the division rated its combat engineer battalion as exhausted.

94th Infantry Division – The division withdrew from its attack zone in central Stalingrad – south of the 71st Infantry Division and north of the 29th Infantry Division (Motorized) – and moved north. The division transferred the 276th Infantry Regiment to the 24th Panzer Division. The division lost ten NCOs/enlisted killed in action; ten NCOs/enlisted were wounded in action. The division reported that of its seven infantry battalions, all seven were weak in combat power; the division rated its combat engineer battalion as average.

Battle Group Stahel – The battle group defended northwest of Orlovka to contain enemy forces. To the southwest was the 389th Infantry Division; to the northwest was the 16th Panzer Division.

XVII Corps

79th Infantry Division – The division defended in sector from Bol’shoy-Verkhne-Kalmykovskii-Verkhne-Fomichinskii-Baskowskij, against the 124th Rifle Division. The division headquarters was located at Karagichev. To the west was the XXXV Italian Corps; to the east was the 6th Romanian Infantry Division. The division reported that of its six infantry battalions, four were average and two were weak in combat power; the division rated its combat engineer battalion as average.

113th Infantry Division – The division swung north and moved toward the rear of the 76th Infantry Division. The division reported that of its eight infantry battalions, six were strong, one was medium-strong and on was exhausted in combat power; the division rated its combat engineer battalion as medium-strong.

298th Infantry Division – The division occupied three assembly areas along the Sixth Army’s western boundary and south of the 79th Infantry Division.

1st Romanian Cavalry Division – The division defended in sector near Molologowskij against the 76th Rifle Division and 63rd Rifle Division. To the west was the 13th Romanian Infantry Division; to the east was the 376th Infantry Division.

1st Romanian Armored Division – The division occupied an assembly in the western part of the corps sector.

5th Romanian Infantry Division – The division moved to the north of the 1st Romanian Armored Division.

6th Romanian Infantry Division – The division defended in sector south of the Don River against the 96th Rifle Division. To the west was the 79th Infantry Division; to the southeast was the 13th Romanian Infantry Division.

13th Romanian Infantry Division – The division defended in sector along the Don River west of Kletskiy against the 278th Rifle Division and the 63rd Rifle Division. To the northwest was the 6th Romanian Infantry Division; to the east was the 1st Romanian Cavalry Division.

XXXXVIII Panzer Corps

14th Panzer Division – The division conducted consolidation operations in sector. To the north was the 29th Infantry Division (Motorized); to the south was the 371st Infantry Division. The division lost one officer and nine NCOs/enlisted killed in action; 62 NCOs/enlisted were wounded in action; three NCOs/enlisted were reported missing in action.

29th Infantry Division (Motorized) – The division conducted consolidation operations in sector. To the north was the 71st Infantry Division; to the south was the 14th Panzer Division. The division lost five NCOs/enlisted wounded in action; one NCO/enlisted was reported missing in action. The division reported that of its six motorized infantry battalions, three were medium-strong and three were average in combat power; the division rated its combat engineer battalion as strong and its motorcycle battalion as strong.

71st Infantry Division – The division, now subordinated to the XXXXVIII Panzer Corps, defended in its sector against the 13th Guards Rifle Division, with the 29th Infantry Division (Motorized) to the south and the 295th Infantry Division to the north. The division reported that of its eight infantry battalions, one was weak and seven were exhausted in combat power; the division rated its combat engineer battalion as average.

LI Corps – The 101st Heavy Artillery Detachment and the 616th Heavy Artillery Detachment were assigned to support the corps. The corps suffered the following officer casualties: five killed in action; 30 wounded in action.

24th Panzer Division – The division initially repulsed an enemy attack on its positions and then continued to attack north in zone, seizing Silikat Factory Nr. 3 against the 112th Rifle Division. The division received the attachment of the 276th Infantry Regiment from the 94th Infantry Division. The division suffered two officers and 22 NCOs/enlisted killed in action; two officers and 89 NCOs/enlisted were wounded in action. The division reported that of its four Panzer grenadier battalions, two were average and two were weak in combat power; the division rated its combat engineer battalion as average. To the northwest was the 389th Infantry Division; to the south was the 100th Jäger Division.

100th Jäger Division – The division attacked north in zone, seizing the water tower on Hill 102 against the 95th Rifle Division and the 284th Rifle Division, gaining positions in the Krasny Oktyabr Steel Factory Workers’ Settlement and seizing two-thirds of the Meat Combine (west of the “Tennis Racket”). To the north was the 24th Panzer Division; to the south was the 295th Infantry Division. The division suffered three officers and 67 NCOs/enlisted killed in action; five officers and 271 NCOs/enlisted were wounded in action. The division reported that of its four Jäger infantry battalions, all four were strong in combat power; the one Croatian infantry battalion was strong in combat power; the division rated its combat engineer battalion as medium-strong.

295th Infantry Division – The division attacked in zone on and near Hill 102 against the 95th Rifle Division and the 284th Rifle Division. To the north was the 100th Jäger Division; to the south was the 71st Infantry Division. The division lost 16 NCOs/enlisted killed in action; two officers and 42 NCOs/enlisted were wounded in action. The division reported that of its seven infantry battalions, four were weak and three were exhausted in combat power; the division rated its combat engineer battalion as average.

389th Infantry Division – The division attacked northeast in zone, protecting the flank of the 24th Panzer Division and seizing the edge of the Barrikady Gun Factory Workers’ Settlement against the 308th Rifle Division. To the east was the 24th Panzer Division; to the northeast was Battle Group Stahel. The division suffered three NCOs/enlisted killed in action; ten NCOs/enlisted were wounded in action. The division reported that of its six infantry battalions, all four were weak in combat power; the division rated its combat engineer battalion as weak.

Fourth Panzer Army

IV Corps

297th Infantry Division – The division defended in sector against the 157th Rifle Division and the 154th Marine Infantry Brigade. To the north was the 371st Infantry Division; to the south was the 20th Romanian Infantry Division.

371st Infantry Division – The division defended in sector north of Peschanka to Elkhi against elements of the 422nd Rifle Division. The division headquarters was located west of Staro-Dubovka. To the north was the 14th Panzer Division; to the south was the 297th Infantry Division. The division suffered eight NCOs/enlisted killed in action; one officer and 27 NCOs/enlisted were wounded in action.

20th Romanian Infantry Division – The division defended in sector north of the Volga-Don Canal against the 154th Marine Infantry Brigade and the 38th Rifle Division. To the north was the 297th Infantry Division; to the south was the 2nd Romanian Infantry Division of the VI Romanian Corps.

Stalingrad Excerpt 2

Letter from Unteroffizier Kurt Helbig, 9th Company, 54th Jäger Regiment, 100th Jäger Division, written on October 11, 1942. The letter from Stalingrad reads in part:

“Health-wise I am OK and I thank God for it, because the fighting here is very vicious. Even right now, it is a hot situation outside…When I look outside of my bunker, I have a view of the city and the Volga River. But honestly, I rather would like to be far away from here and hope that the war will be over soon. The Russian is a very hard enemy…The nice summer has gone too, and the cold Russian winter knocks on the door. I do not look forward to it. I don’t think there is a chance to get out of here.”

Letter from Obergefreiter Ludwig Hebestreit, dated November 11, 1942, to a comrade back home. Ludwig was assigned to the 2nd Company, 1st Battalion, of the 212th Infantry Regiment in the 79th Infantry Division. In his letter from Stalingrad, he writes:

“I wonder if you can do me a favor, since October 10, I have not heard a word from Linz, no mail; nothing. Could you please call there and find out what is going on? I am worried, inasmuch as Hannelore is now in Wiener Neustadt. Many thanks. Let me say that we have a lot of worries of our own. Since I sent you my last letter in October, I am at the Stalingrad front; there is hot fighting here; I just cannot describe it. But one thing is for sure; if the Russians tie this sack up, we can say, “The fire has gone out for us.” Our company has 47 able-bodied men left; seems to be a good strength? Well, a neighboring Agramer Battalion [369th Infantry Regiment] has only 80 men left. There is no way back, only forward, stubborn “Heil,” Führer Orders, we follow it seems. The fighting here is down to knives, for every house, every floor, and every room and at times for any small corner that givers cover. On top of it, winter has arrived and God knows what is in store for us. Well, Seppl, do me this favor, and if all is well, let me know.”

Letter, dated December 20, 1942, from “Rudi” to his girlfriend Maria in Mainz. Rudi was a lieutenant and the commander of the 13th Company in the 669th Infantry Regiment of the 371st Infantry Division. He was wounded within a few days, flown out of the pocket on December 30, 1942 and later recovered from his wounds at a military hospital in Gütersloh, Germany. In his letter, he writes:

“And once again, a day comes to an end in dust and dirt, plus a biting cold. For writing paper, I use a page from my Service Book, so what, nobody will ever ask for it here now. My other belongings I had to leave behind in a bunker that now is buried under tons of earth. I am now in a fodder cellar under a ruined house, but there is no fodder here, not for us; the last warm soup we had 4 days ago and now we live on bread and some tea. The snow makes the water, the tea we found on a dead Russian. This morning, we retreated to here; tomorrow, we are supposed to go further back, where we will get food and mail, we hope. Maybe this letter will find you then after all. Nobody speaks of Christmas, I cannot give you any hope it seems; we were sold down the river, short and sharp. I will try to write as best as it is possible and, of course, when the mail works. I still have 28 men; that is all from 90.

What is the use of a Service Book here; I will swap 1 week in Stalingrad anytime for 5 years in prison at home. Remember the sign above the entrance to Hell.

‘Drop all hope’

Correct, we have done so, ever since August; greetings to my homeland.”

Letter, dated December 23, 1942, from Obergefreiter “Mathias” to his sister. Mathias was assigned to the butcher company of the 371st Infantry Division. He writes:

“This letter will be delivered in person by a comrade who was flown out of here because of a wound. So my comrade Karl Pütz will bring this letter. I am wounded also, but it is just a minor wound from shrapnel in my left arm. So, I sincerely hope that this letter will reach you; the paper is the last I have; the cover is from the writing tablet. Now I hope you have a nice Christmas. We will celebrate ours in a cellar, which is a bit safer. We are supposed to get good bread and marmalade tomorrow.

This morning we killed the last horse we had. I pity the creature, but it would have died of hunger soon. Four weeks ago, I was still a human being; now we are dirty and covered with lice; soldiers, who are hiding in Stalingrad, half-frozen and hungry and there is no way forward or backward. Whether we ever get out of here, only dear God will know. If not, there is only death or being taken prisoner. Since I got here, there has not been one day of peace. If the enemy is not attacking, he showers us with artillery and machinegun fire. Dear Hedel, in the event that I never come back, I say farewell. But my hope is that I become a prisoner, as one day the war will end. Those of us who are still alive then, will return home.”