Maskirovka

For centuries, the Russian empire, especially her military, have brought deception to a fine art. The Russian word maskirovka, translating to “masking something”, is designed to manipulate the enemy’s decision-making process so it does, or doesn’t, take actions, which therefore enhance the likelihood of Russian success. These actions might be reinforcing a certain sector of the front, thinking the Russians will attack there, when the Russians all along were going to attack somewhere else – and where the Russians really do attack, now has few enemy troops. Effective deception – maskirovka – often results in achieving surprise, one of the key principles of war.

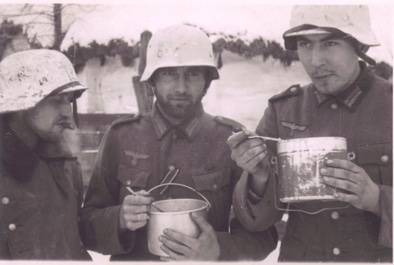

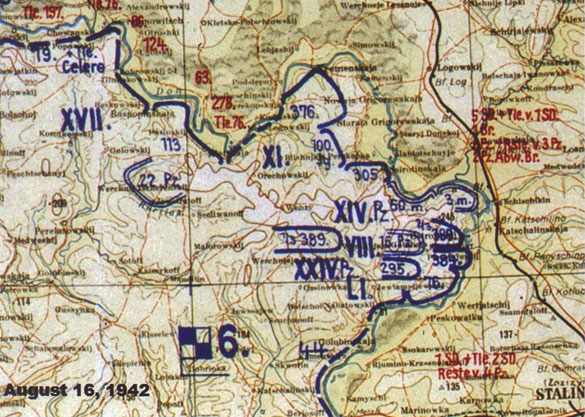

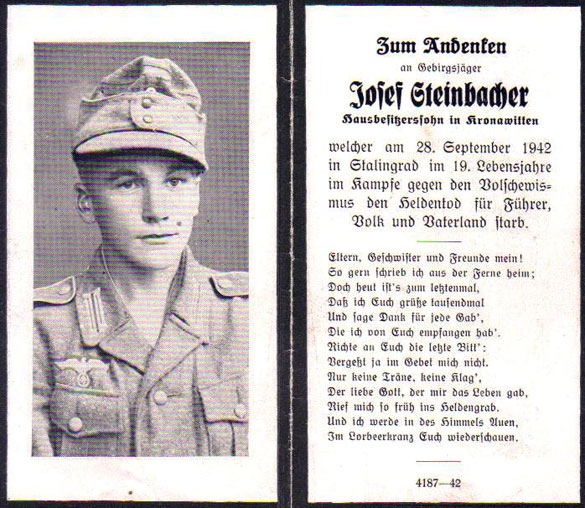

It is not enough to just fool the enemy; there must be actual actions that the enemy takes in response to that deception. At Stalingrad in 1942, the Russians portrayed the situation in the Soviet city as on the edge of falling for several months, by only bringing in relatively small reinforcements across the Volga River from Soviet positions east. The Germans, in turn, pulled additional German units in from the flanks north and south of Stalingrad for a final push, and let Romanian, Hungarian, and Italian units take over those flank defensive sectors. Then in mid-November 1942 – wham, the Russians attacked those flanks, surrounding Stalingrad, where the German Sixth Army died on the vine over the next 75 days, a major turning point in the war.

The first precept of maskirovka is to “give the enemy the smell that he likes,” an Israeli army colonel once told me. Every enemy has a preconceived notion of how the battle is probably going to unfold; identify that and use that as the deception story – the false scenario and how it will play out. The enemy wants to believe that they guessed right, so all deception measures should reinforce those enemy’s biases. In World War II, the Germans believed the Western Allies would invade France from England at the Pas-de-Calais area of France. First, because the English Channel is at its narrowest at this point, but more importantly, because it was from Pas-de-Calais that Germany intended to invade England in 1940. Therefore, all Allied deception measures were designed to “sell” a Pas-de-Calais invasion, hiding the real invasion at Normandy, where the distance across the Channel was five times that of Pas-de-Calais, and in German minds you’d have to be crazy to try that.

Conceal the real; portray the unreal is the second guide. Not only does good maskirovka depict false operations, but includes tight operational security to hide what is really going on, because if the enemy obtains evidence of your legitimate plan, they may not fall for the deception to hide it. Disseminating battle plans on a strict “need to know” reduces the possibility that those plans get “leaked.” Anything that is leaked, should only be the false battle plans – and then disclosed only in a believable manner. That is sometimes done by double agents – an enemy agent that has been apprehended, threatened with death, and “turned”, so the agent, in addition to feeding inconsequential true intelligence to keep credibility with his original clients, is fed elements of the deception story: “Joe has always given us good information, so this must be good too.”

It isn’t just human intelligence (spies) that is necessary to execute maskirovka effectively; you have to “fool” all the battlefield sensors of the enemy. This includes radar and other electronic detection devices, and aerial photography – and in World War II there were no satellites to fool; now there may be 8,000 in orbit. Audio sensors listen for certain sounds; sensors on the Internet monitor everything from what kind of mouthwash you buy online, to actions that indicate you are probably a firearms’ owner. Motion sensors can measure the movements of deer, or movements of military tanks. If you attempt to shoot down every enemy drone in an area, your opponent may believe correctly that you are up to something in that area. But if make no attempt to shoot down any drones over an area, because you want them to pick up indicators of activity, the enemy might ask themselves why you are allowing those drones to operate.

How do you know what to look for concerning maskirovka? An enemy can portray tank columns moving in certain directions that have nothing to do with the real attack. They can drop leaflets warning citizens to evacuate a certain area when no attack is actually going there. What are difficult to hide are logistical functions. Show us where the fuel points are, and we can determine how many armored vehicles that supports and the area they will operate. Sure, the enemy could deploy empty 55-gallon drums of ‘fuel” at a fake fuel depot as deception, but an empty drum will have a different thermal signature from one filled with diesel.

For discovering maskirovka operations in the field of political tricks remember the old adage: “follow the money.” But with money now measured by electrons (there are no actual greenbacks in what your bank calls your checking account), that can be difficult, and of course hacked and an account made to look larger or smaller with a couple of keystrokes. But there’s always some idiot that drops off a damaged MacBook laptop at a Delaware computer store to be repaired, and on that computer are various trails of money paid for nefarious deeds, with money trails up to the highest levels possible. Maskirovka? Or real? Constructing fake dossiers (portray the unreal) is another element of maskirovka, and one that was done successfully by the Germans against the Russians, providing Stalin’s intelligence services with fake “evidence” that his generals were about to overthrow him. Stalin bit, and had hundreds of loyal generals shot.

Deception plans of maskirovka are some of the most sensitive, tightest “need to know” restrictions of all. Even knowing that some type of deception is going on is tightly controlled to the point that often high-level decision-makers are in the dark. While it was not part of the deception plan, Vice President Harry Truman was not told about the Manhattan Project – the development of the atomic bomb – until hours after he became President after FDR’s death.

Today, the Russians are still at it with respect to maskirovka, whether that is in the Ukraine, or whether that is interfering with foreign economies and politics by injecting false stories into news cycle, or even potentially manipulating U.S. election results. Can’t happen here? Nobody’s that smart. If you think the Russian aren’t good at maskirovka, ask the roughly 250,000 Germans at Stalingrad who never came home.

Or just watch Operation Mincemeat on Netflix to see the depths of details that have to be accomplished to sell a deception effort.