Simon Wiesenthal

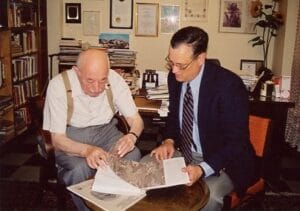

I was just reorganizing my desk and found some photographs almost twenty years old. One was a picture from July 2002 when I was fortunate enough to meet Mr. Simon Wiesenthal in his office in Vienna.

Simon Wiesenthal (above in his later years) was born on December 31, 1908, in Buchach, in the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, which was then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. His father was a wholesaler, who had left Russia in 1905 to escape the anti-Jewish pogroms. The elder Wiesenthal was called to active duty in 1914 in the Austro-Hungarian Army at the start of World War I; he was killed in action on the Eastern Front in 1915. Simon, his younger brother and his mother fled to Vienna, when the Russian Army overran Galicia. In the ebb and flow of war, the family returned to Buchach in 1917, after the Russians retreated. Simon attended the Czech Technical University in Prague, where he studied from 1928 until 1932. After graduating, he became a building engineer, working mostly in Odessa in 1934 and 1935. The next six years are unclear, concerning Wiesenthal’s life; he married in 1936, when he returned to Galicia.

After the Nazi invasion of Russia in 1941, Wiesenthal’s mother came to live with him and his wife in Lvov. Wiesenthal, a Jew, was detained by German authorities on July 6, 1941, but was saved from an Einsatzgruppe firing squad by a Ukrainian man, for whom he had previously worked. German police deported Wiesenthal and his wife in late 1941 to the Janowska labor and transit camp and forced to work at the Eastern Railway Repair Works. Every few weeks the Nazis would conduct a selection of Lvov Jewish Ghetto inhabitants unable to work. In one such deportation, Wiesenthal’s mother was transported by freight train to the Belzec extermination camp and killed in August 1942. On April 20, 1943, Wiesenthal avoided execution at a sand pit by firing squad, when at the last moment a German construction engineer intervened, stating that Wiesenthal was too skilled to be killed.

On October 2, 1943, the same German warned Wiesenthal that Janowska and its prisoners were about to be liquidated. Wiesenthal was able to sneak out of camp and remained free until June 13, 1944, when Polish detectives arrested him in Lvov. With Russian troops advancing, the SS moved Wiesenthal and other Jews by train to Przemyśl, 135 miles west of Lvov, where they built fortifications for the Germans. In September 1944, the SS transferred the surviving Jews to the Płaszów concentration camp in Krakow. One month later, Wiesenthal was transferred to the Gross-Rosen concentration camp. While working at a rock quarry there, Wiesenthal was struck on the foot by a large rock, which resulted in the amputation of the large toe on his right foot. The advancing Russian Army forced the evacuation of Gross-Rosen; Wiesenthal and other inmates marched by foot to Chemnitz. From Chemnitz, the prisoners were taken in open freight cars to Buchenwald. A few days later, trucks took the prisoners to the Mauthausen concentration camp, arriving in mid-February 1945. When the camp was liberated by American forces in May 1945, Wiesenthal weighed 90 pounds.

Wiesenthal dedicated most of his life to tracking down and gathering information on fugitive Nazis. His goal was to bring as many conspirators to the “Final Solution” as possible to justice for war crimes and crimes against humanity. In 1947, Simon Wiesenthal co-founded the Jewish Historical Documentation Center in Linz, Austria, in order to gather information for future war crime trials. He later opened the Jewish Documentation Center in Vienna. Wiesenthal was instrumental in the capture and conviction of Adolf Eichmann.

The author interviewed Simon Wiesenthal at his small office in the Jewish Documentation Center in central Vienna in July 2002. During the visit, Mr. Wiesenthal said that there was one thing wrong with his book, The Camp Men. Dismayed, French waited for the explanation. “You were born 50 years too late. You found how to look through their officer files to prove they had been in the camps, while I had to rely on eye-witnesses. If you had been there to help me back then, I would have found more. But you weren’t born yet!”

Wiesenthal wrote The Sunflower, which describes a life-changing event he experienced when he was in the camp. He died in Vienna on September 20, 2005; his remains are buried at Herzliya, Israel.