Heinrich Müller was born in Munich, Bavaria, 28 April 1900, the son of working-class Catholic parents. In the final year of World War I, he served as a pilot for an artillery spotting unit, during which he was decorated several times for bravery, to include the Iron Cross 2nd Class, the Iron Cross 1st Class, the Bavarian Military Merit Cross 2nd Class with Swords and the Bavarian Pilots Badge.

Müller joined the Bavarian Police in 1919. During the immediate post-war years, Müller was involved in the suppression of attempted Communist risings in Bavaria (He became a lifelong enemy of Communism after witnessing the shooting of hostages by the revolutionary “Red Army” in München, during the Bavarian Soviet Republic.) During the Weimar Republic, Müller served as the head of the München Police Department, where he acquainted with many members of the Nazi Party including Heinrich Himmler and Reinhard Heydrich.

After the 1933 Nazis rise to power, Heydrich – as head of the Security Service – recruited Müller to the SS. In 1936, as head of the Gestapo, Heydrich named Müller that organization’s Operation’s Chief. Heinrich Müller quickly rose to the ranks, achieving the grade of SS-Gruppenführer in 1939. With the consolidation of law enforcement agencies under Heydrich in the Reich Main Security Office (RSHA), Müller became the chief of the RSHA “Amt IV” (Office #4 or Deptartment #4.) At about the same time, he acquired the nickname “Gestapo Müller” to distinguish him from another SS general of the same name. The nickname would soon bring an aura of dread associated with Müller for many. He was also called “Bloody Müller.”

As the Gestapo chief, Heinrich Müller played a leading role in the detection and suppression of all forms of resistance to the Nazi regime, succeeding in infiltrating and destroying many underground networks of the Communist Party and the Social Democratic Party. Müller was also active in resolving the Jewish question; Adolf Eichmann headed the Gestapo‘s Office of Resettlement and then it’s Office of Jewish Affairs (the Amt IV section called Referat IV B4), as Müller’s subordinate. Müller attended the Wannsee Conference in Berlin in January 1942 that formalized responsibilities for the destruction of Europe’s Jews.

In 1942, Müller successfully infiltrated the “Red Orchestra” network of Soviet spies and used it to feed false information to the Soviet intelligence services. While not the commander of any Einsatzgruppe, he received regular reports on their progress in Russia. In February 1943, he presented Heinrich Himmler with firm evidence that Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, chief of the German Abwehr Military Intelligence Organization, was involved with the anti-Nazi resistance; however, Himmler told him to drop the case. During the war, Müller received the Knights Cross of the War Service Cross.

After the failure of the July 20, 1944 Bomb Plot to assassinate Hitler, Müller assumed responsibility, for arresting and interrogating anyone suspected of involvement. Müller’s agents arrested over 5,000 people during the next six months. In April 1945, Müller was among the last group of Nazi loyalists assembled in the Führer Bunker, as the Soviet Army fought its way into Berlin. One of his last tasks was to interrogate SS-Gruppenführer Hermann Fegelein in the basement of the Church of the Trinity, near the Reichs Chancellery. Fegelein was Himmler’s liaison officer to Hitler and after Müller’s interrogation, he was shot on April 28, 1945 on Müller’s evidence that Fegelein was attempting to flee Berlin.

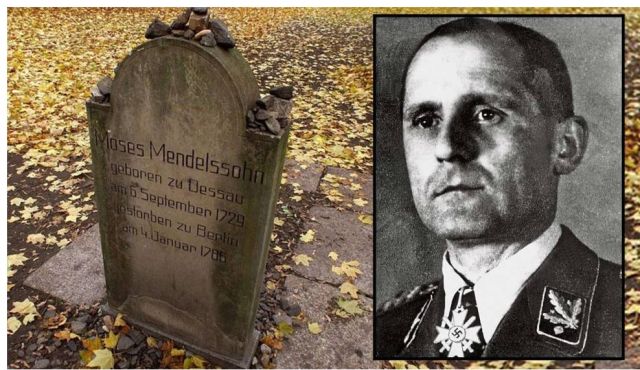

Müller’s fate has been the subject of speculation; many historians believe that he was killed, while others opine that he worked for the Soviet Union or the United States Central Intelligence Agency after the war. Other theories speculated that he escaped to South America. The most intriguing option of Müller’s fate came from Walter Lüders, a former member of the Volkssturm (Peoples’ Defense Force.) Lüders said that he had been part of a burial unit, which had found the body of an SS General in the garden of the Reich Chancellery, with the identity papers of Heinrich Müller. The body was subsequently buried in a mass grave at the Old Jewish Cemetery on Grosse Hamburger Strasse, then in the Soviet Occupation Sector.

There appears to have been no investigation of this gravesite since the war to assess the validity of this witness. Speculation continues, with the recent book Grey Wolf postulating that Müller was part of an elaborate escape plot that ended in Argentina. In any case, “Gestapo Müller” once boasted, “I’ve never had a man in front of me yet whom I did not break in the end.” Was Müller broken in death at the end of the war or did he escape?