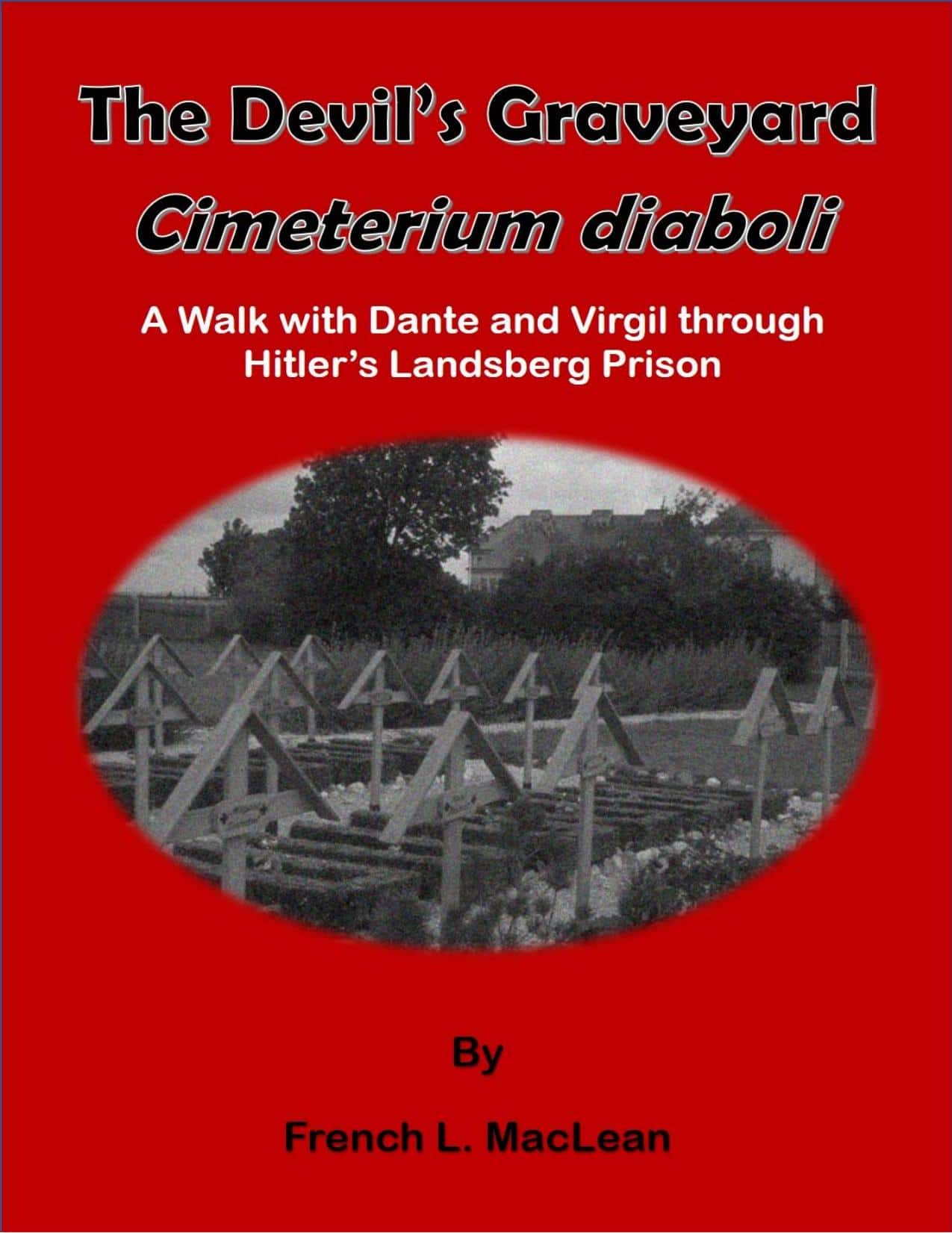

The Devil’s Graveyard

Prologue

Massive, thick, squatty, gray, with a red-tiled roof the color of dried blood, the Landsberg Prison is of the Art Nouveau design, but its countenance is something medieval, something horrid. With an entrance building three stories high, the two round corner towers are topped with weathered copper onion domes, so common in Bavaria. The copper patina has turned to light green, streaked with black oxidation. The building itself is a depressing gray. The overall effect of the scene is of something from the harsh east, something out of the depths of Asia, where cruelty is a way of life.

One-hundred yards away is a small cemetery, known as the Spöttinger Friedhof. On its grounds are row upon row of crosses. Each cross is stark, made of wood and topped by an inverted “V” that looks like a tiny roof. To a German, nothing is out of place; to a foreigner, the crosses appear to be the boney cores of scarecrows. A closer examination reveals that most of the crosses have had their nameplates removed. Someone is buried under each marker, but we are not supposed to know whom that might be.

The combination of prison and cemetery is linked by history as well as proximity. For six years following World War II, hundreds of Nazi war criminals were confined to the prison. They had been tried and sentenced at other locations – primarily Dachau and Nürnberg – but were transferred to Landsberg to serve anywhere from one year to life. Almost 300 had a different fate in store – they would be executed by firing squad or by hanging. Those, whose families did not request their remains, were buried at the cemetery.

These criminals were the worst of the worst. They lynched downed American airmen. They conducted painful, horrible medical experiments on helpless concentration camp inmates. They shot tens of thousands of “sub-humans” in the Einsatzkommandos in the snows of Russia. They threw the dead and the near dead into the crematoria ovens and furnaces at Auschwitz, Buchenwald and Dachau. Were Dante Alighieri alive in the twentieth century, rather than seven centuries ago, he would have populated his nine circles of Hell with these men in an updated Dante’s Inferno.

Perhaps Dante could do this from the grave. There is something about this area of Bavaria – some thirty miles west of Munich. The most evil man of the last century resided here for a while. Adolf Hitler served several years’ incarceration in this same prison after his failed putsch. He dictated his horrendous Mein Kampf, which stated within its pages his ultimate plan to kill Jews and other sub-humans, from his cell room. There is a constant, nagging feeling in the cool air that this location is a portal from one time-period to another. Time travel – at least in one’s active imagination – is possible here. The graves and the prison seem to try to pull us back into a terrible time. There is something evil here. Could this be a portal to the past?

“Salve! Dante, welcome to the twentieth century. My name is Virgil; we have met before. Welcome to the Devil’s Graveyard.”

“It is good to see you again, Virgil. What year is it and why have you come for me?”

“It is about seven hundred years after you died, Dante. Much has happened since then. Your city-states have all joined as one country, known as Italy. From Sicily to the Alps is now one nation, speaking one language, using one currency.”

“And they get along alright, Virgil? I mean, are they not at each other’s throats?”

“Yes, Dante, they are fine, although they still argue about politics and who is more corrupt than another. They argue about food, sports, wine and women. You would feel right at home in Italy.”

“But we are not in Italy, Virgil. I feel a cool wind here, a rawness not known to the south.”

“Yes, this is Germany, Dante; we are north of the Alps in the land of Frederick Barbarossa – Germania, as you knew it. The reason I have brought you here is that for many years after your death, mankind remained, as you knew it. Lust, gluttony, greed, anger, heresy, violence, fraud and treachery remained pretty much the same, generation after generation. Thus, the nature of Inferno, as you called it – others refer to it as Hell – remained the same, as mankind never seemed to learn from the mistakes of the past and kept repeating them. However, in the last century, something dreadful changed. For twelve years, mankind went insane and committed sins that dwarfed anything you could have comprehended from your day. Tens of millions of people were murdered in these dozen years. Over one hundred million people suffered some form of deprivation. Many humans killed and plundered during this time, but it seemed that a group of men from Germany became the worst of the worst. Because of them, mankind became aware of evil in a different scope than perhaps ever before. It was only natural that with a different level of evil men, Hell changed as well. You might say that Hell had to modernize its character and way of doing business.”

“So we are going to Hell, Virgil?”

“Yes, in a manner of speaking, Dante. We will visit the various circles of Hell, much as we did in your epic work of literature so many years ago. However, it is also instructive to meet the worst offenders here on Earth, so you can see and hear them in their human corpus form, before they actually make their way to their appropriate destiny in the underworld. Therefore, we will be traveling through time to various places here in Germany – and to Poland for that matter – although most of our time will be spent here at the town of Landsberg.”

“Facilis descensus Averno – Virgil – Easy is the descent into Hell. But why will we be in Landsberg so often, Virgil?”

“The evil men started a war that lasted about six years. At the end of this war, the malevolent men lost and the victors tried several thousand people for crimes against humanity, which they defined as particularly odious offenses against human dignity, to include murder, deportations, medical experimentation and forced emigration. The victors found hundreds of men, and a few women, guilty of some or all of these particulars and executed almost three hundred of the condemned right here at this prison.”

“Will we go anywhere else, Virgil? So we will visit the circles of Hell once again?”

“Yes, Dante, we will go back to the underworld. That is why I was sent here as well. The angel Gabriel is concerned. You see, there have always been portals to the underworld, usually at places on Earth, where evil was at its worst. These portals are two-way avenues and unfortunately allow the demons to come out of Hell to terrorize the living. The portals never go away and it appears that there are now more than when you were alive. Gabriel believes that once so many portals are created, there could be great peril on the Earth. In fact, these evil men in Germany were so wicked that four new portals were created during their reign. The last is here at the Landsberg Prison. The others are now beneath Berlin, Auschwitz and Lublin – these last two are in Poland. They are on this old German map that Gabriel provided me, which also shows occupied Poland on the right and the united Austria in the green at the bottom. Our journey will take us to all of them. Do not worry about all the German words such as Reichsgaue; I will explain everything in due time. We will go in other, newer ways of transport and you will save your strength and enjoy them all, I promise you. Are you ready to begin?”