The Fifth Field

The Story of the 96 American Soldiers Sentenced to Death and Executed in Europe and North Africa in World War II

The Fifth Field: reveals one of the final secrets of the war, how 96 American soldiers in Europe and North Africa were tried by American General Courts-Martial, convicted by military juries, sentenced to death, executed and buried in an obscure, secret plot at an American military cemetery in France. Their case files remained in a dark closet until after Nine-Eleven, almost like the Ark of the Covenant at the end of Raiders of the Lost Ark. Eat your heart out Harrison Ford; this was the real mystery solved. “A ‘Rosetta Stone’ for every future historian researching and writing about Army courts-martial in World War II” says the Judge Advocate General Center and School Historian.

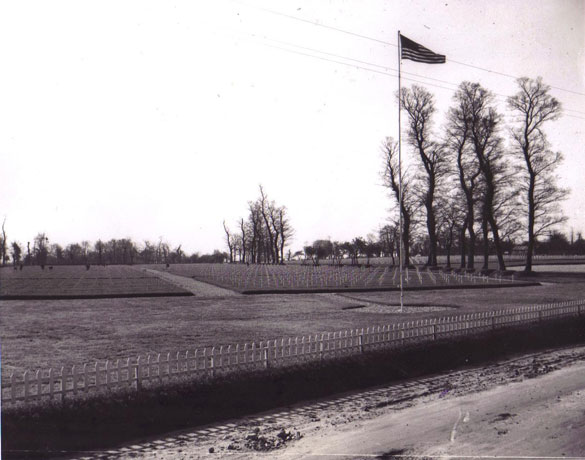

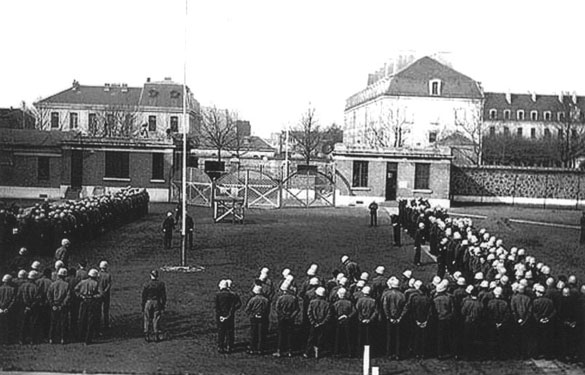

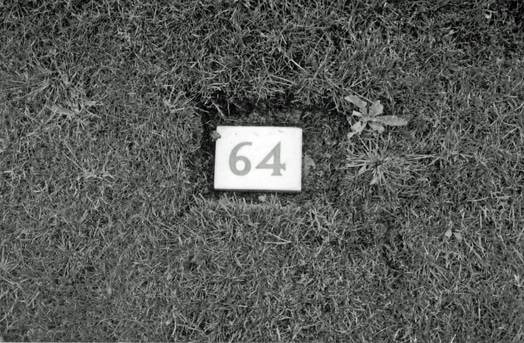

A non-fiction book, but you will swear you are reading a mystery fiction thriller. It begins with a visit to the cemetery, where to this day – seven decades after the war – their small flat gravestones bear only the numbers 1-96, not names, chiseled into them.

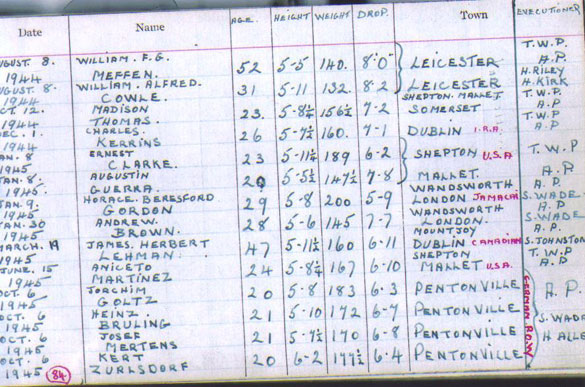

These were not crimes against enemy soldiers or against civilians actively supporting the enemy. These 96 soldiers murdered 26 fellow American military personnel, and killed or raped 71 British, French, Irish, Italian, Polish and Algerian civilians, in addition to the one soldier executed exclusively for desertion.

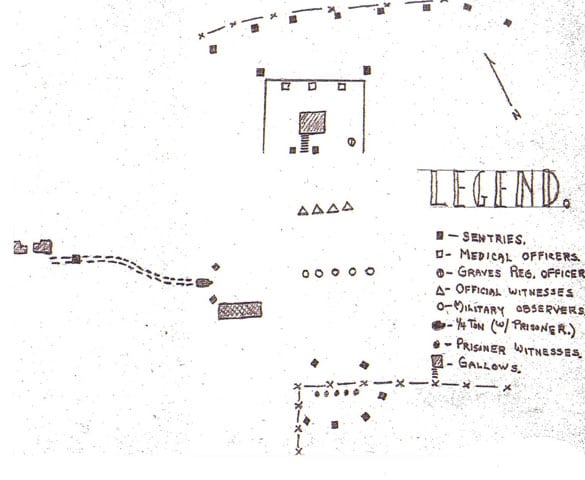

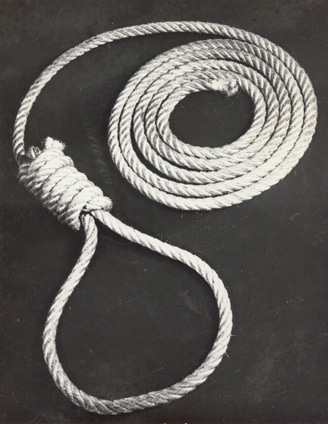

The executions were not ad hoc, shot-while-trying-to-escape killings. Every single verdict had been personally approved by General Dwight D. Eisenhower or another high-ranking Theater Commander. Many of the executions occurred in the French villages, where previously the crime had occurred. There were no last-minute opportunities to avoid the noose by volunteering for a suicidal mission à la the fictional account of condemned soldiers in The Dirty Dozen, although one American general, as discussed in the book, really did propose something similar.

The actual cases are the stars of the book. The public really only knows of one – Eddie Slovik – and knows little of the process involved. The courts-martial, some of which started just five days after the commission of the crime, were to the point and strict (“if the glove won’t fit, you must acquit” tactics were not allowed); some proceedings took as little as one hour. Judge Advocate reviews then took a few weeks, although the defendant had no legal representation, nor did he appear at these later proceedings.

Surprisingly, the Army found that it had no qualified hangman, so English hangmen conducted 16 executions for crimes committed in Britain, but British hangmen could not serve outside England. Matters became so serious that Eisenhower ordered a U. S. Army brigadier general to hang four condemned soldiers one chilly morning in Sicily in 1943. The Army finally found a hangman, with claimed experience in Texas and Oklahoma. That was untrue – he had no previous practice, but the Army remained unaware of his deception and promoted him from private to master sergeant in a single day, but he botched at least one-third of the hangings he conducted. Seven of the 96 condemned met their ends by firing squads. Ricochets and bad marksmanship sometimes marred the proceedings.

The Army did its level best to ensure the trials were fair, although a review of the wartime legal system led to significant changes after the conflict. After spending a decade poring over the files – in the author's opinion – three of the soldiers likely were not guilty, ten others were possibly not guilty, while two dozen others could have received life imprisonment and not the death penalty, because of mitigating circumstances.

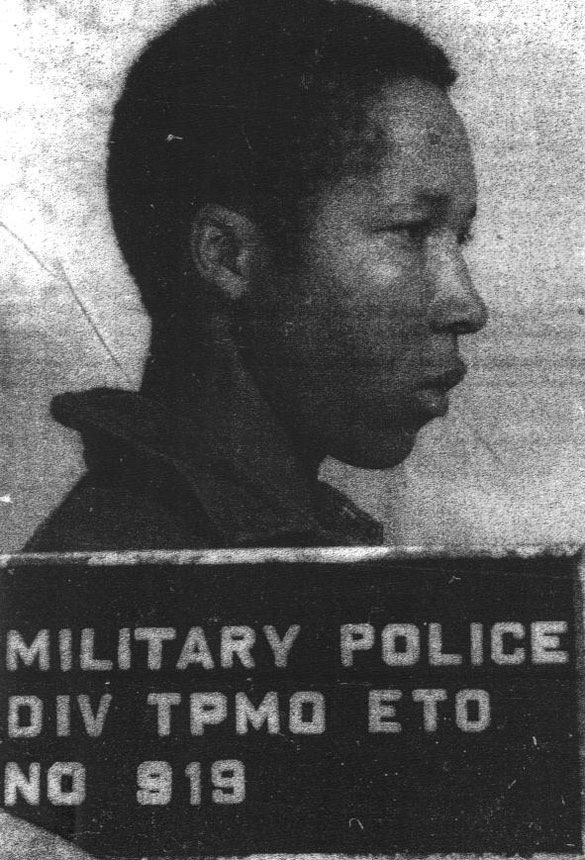

In final research, the author obtained the use of several original photographs of four of the actual executions (two hangings and two firing squads), from the possession of one of the officers at the events in 1945 at the Aversa, Italy Stockade. Photographs of this nature and significance have not been published since the execution of the Lincoln Conspirators in 1865!

Since the book was published, several veterans and family members have contacted the author. One of the murder weapons has now been located and other important information obtained. If you or a family member have any letters, diaries, or old photographs related to this story, please contact the author through the contact page.

Comments on The Fifth Field

“The value of MacLean’s research — which took over ten years to complete — is that it provides a ‘Rosetta Stone’ for every future historian researching and writing about Army courts-martial in World War II. All future research on this topic will lean heavily on this work, and the book’s 62 pages of detailed footnotes will help historians for years to come plough their own ground, be that the study of an individual court-martial or the military death penalty writ large. The Fifth Field deserves to reach the widest possible audience among military historians in general and those with an interest in World War II and military legal history in particular.”

- Colonel Frederick Borch III, US Army Ret., Judge Advocate General Center and School Historian, in The Journal of Military History, April 2014, Volume 78, Number 2

“I couldn’t put it down… a hell of a good book…the subject is fascinating… you have done yeoman’s work and produced a great book.”

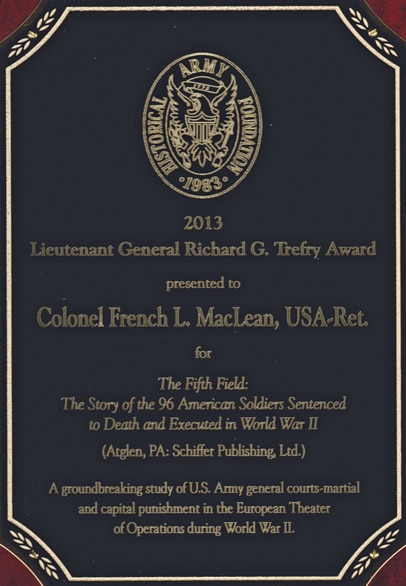

“I had been an enlisted man in World War II and knew that soldiers had been executed, but I did not know how many. Later, when I was the Inspector General of the United States Army, I was visiting the American Military Cemetery in Luxembourg about 1980. As I looked at the crosses, I wondered where the soldiers who were executed were buried. Now, I finally know.”

- Lieutenant General Richard G. Trefry, US Army Ret., Inspector General of the United States Army, Military Advisor to the President of the United States, George H. W. Bush, during the 2013 Army Historical Foundation Awards

Excerpt from The Fifth Field

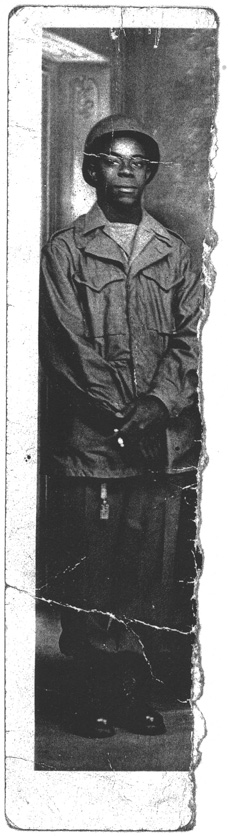

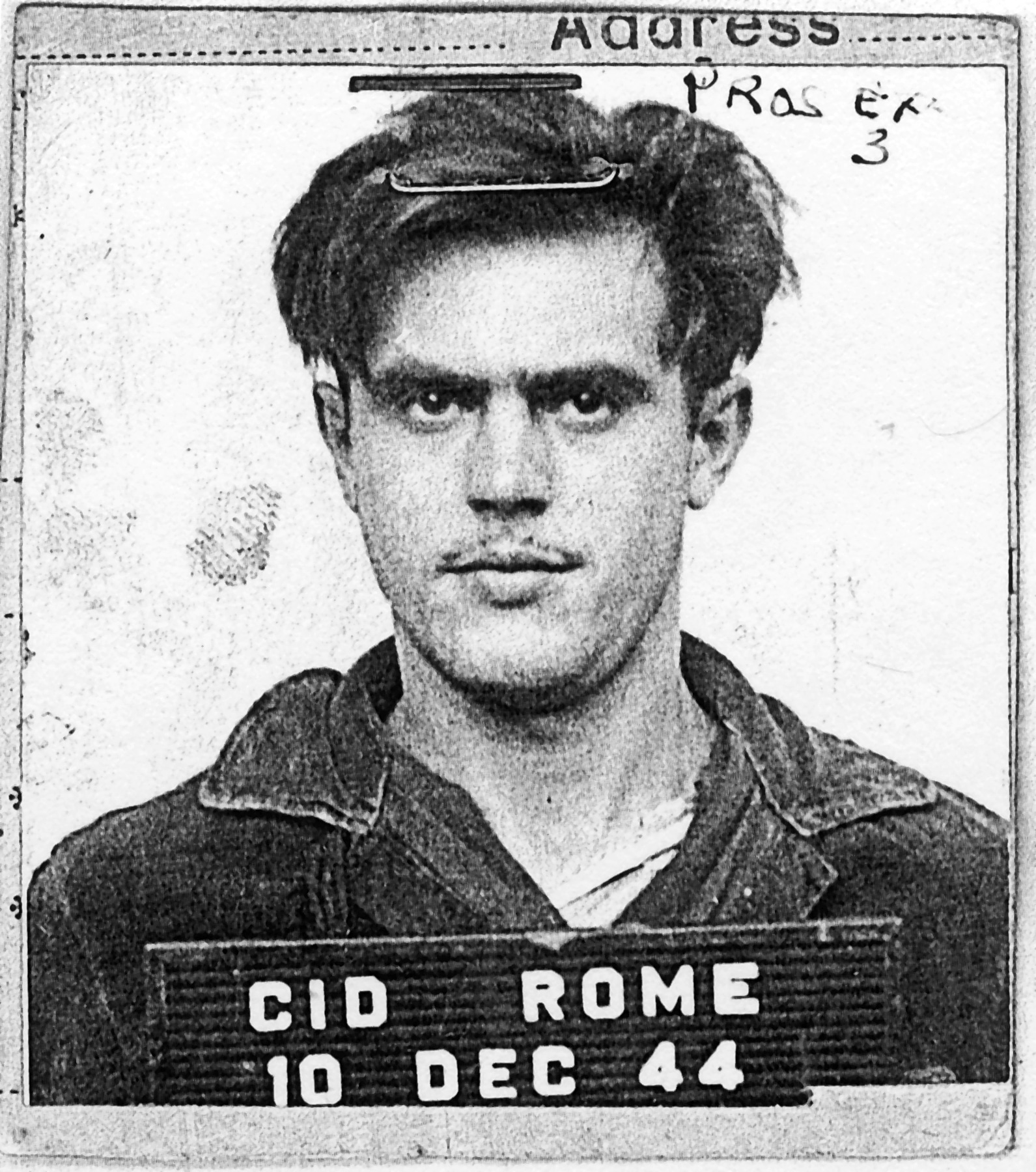

Charles H. Smith was a rough man, a real badass born in Salem, Missouri on October 6, 1909. Smith had a lengthy criminal record, being arrested for speeding and fighting – he was fast with his temper and faster with his fists. Pocket-change offenses, but in 1930, Smith hit the big time, receiving a twenty-year sentence for an unarmed robbery in Granite City, Illinois. He did “seven years on the river” at the Chester, Illinois penitentiary before being released in 1937. Chester – later renamed Menard – Prison, located at the base of a limestone bluff a few hundred yards from the Mississippi River, was a rough old place. It had opened in 1878. From October through April – out in the exercise yard – the wind coming off the ice on “Ol’ Man River” cut through a man’s clothes to the bone. More than half the prison population worked in the stone quarries; it also had an asylum for insane convicts, although in this 122-acre frozen hellhole, everyone was a little bit crazy.

Smith was an inmate at Menard in early 1931, when Murley Johnson – a twenty-six-year-old broom-maker from Mattoon, Illinois – was executed in the electric chair located in the laundry building, for the murder of a woman and her two children. Murley’s final words were “So long, boys.” Menard topped that on December 11, 1931, when the state “fried” Hazel Johnson, Henry Pannier, Willie Green and James Jackson in a single day. Life was rough at Menard, where there was only one guard for every seventeen inmates; perhaps the Army would be a little easier. However, as Charles Smith would find out, after he was inducted at Camp Grant, Illinois on May 11, 1942, the Army could teach the boys at Menard a thing or two about playing rough.

Six months later, on May 7, 1943 at about 7:30 p.m., Private Smith – who had been drinking since 1:00 p.m. – visited the “Villa de Roses,” a house of prostitution in Oran, Algeria. It was not exactly the Ritz; one of the other privates went inside, but said he “didn’t like the looks of the girls” and departed. American MPs patrolled the bordello in case some of the troopers got a little too exuberant. Standing in line, Smith was getting too exuberant – waiting for an hour or two in front of a whorehouse did not bring out the best in a man’s character. The ex-con had his knife out and was showing his fellow soldiers how sharp it was – when a Military Policeman guided him to the front entrance and told him “it was time he was going home.” Smith replied, “You God-damn military pricks don’t give a man to have a chance to have a good time.”

Smith also told the MP, Private Sephus Joe Stinnett, if he came outside, Smith would cut his throat. About that time, another MP walked over, tapped Smith on the shoulder and started to lead him away from the establishment. The MP did not get far. In less than eight steps, Smith whipped out the knife and slashed Corporal William L. Tackett’s throat.