The 800-pound gorillas in the room that could make the establishment of a New Knights Templar difficult are nation states.

One could easily make the argument that the history of mankind has been a violent one. In ancient times, kings and queens could send their empires to war or order the execution of a criminal or political opponent with as little as a nod of the head. Within empires, local tribal leaders often held similar power over life and death.

By the time of feudalism – during the period of the Crusades – European kings depended on loyal vassals to do their bidding and so often turned a blind eye when these vassals sometimes felt the need to do violence to one another over a slight or family grudge. At the same time in Europe, the Catholic Church held great power, and often in consultation with secular rulers, could urge the faithful to “take up the Cross” and go on Crusade with the full knowledge that violence would result. Religious courts also could try individuals on perceived religious violations – such as heresy.

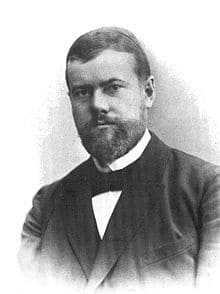

With the rise of the nation state, governments desired to be the sole arbiter of the use of legitimate violence within their borders. This phenomenon was perhaps best described by German philosopher Karl Emil “Max” Weber. The modern state, he believed, emerged from feudalism by expropriating the means of political organization and domination, including violence, and by establishing the legitimacy of its rule. Writing during the period 1890 to 1920, Weber – in his work – Politics as a Vocation, Weber defined a concept he termed Gewaltmonopol des Staates (Monopoly of Power of the State) as any organization that succeeds in holding the exclusive right to use, threaten, or authorize physical force against residents of its territory, which was most seen at the level of a nation state. According to Weber, this could only occur via a process of legitimation of that organization. He then went into detail that this social authority was most often seen in three forms, which he labelled as charismatic, traditional, and rational-legal.

According to Max Weber, the state was the source of legitimate physical force, with the public police and the military as its main instruments; he also added that private security could also be used with state authorization. Weber delved into several levels concerning the monopoly of force, believing that this did not mean that only the government could use physical force, but that the state was the only source of legitimacy for all physical coercion or adjudication of coercion. This would provide citizens with the backing of law when individuals found themselves in a situation requiring the use force in defense of self or property; the right derived from the state’s authority. This fits with other philosophers’ views that the state can grant another actor the right to use violence without losing its monopoly, as long as it remains the only source of the right to use violence.

As nation states progressed, many expanded on this theory and in many cases desired that they have a monopoly on the potential to use force. Starting with totalitarian régimes, governments began to limit ownership of firearms – stating that weapons were the root cause of violence – but in actuality believing that an unarmed citizenry will be a docile citizenry. Over the last half century, these policies have been adopted in traditional democracies. England – the home of the Magna Carta, actually enacted The Unlawful Games Act in 1541 that required every Englishman between the ages of 17 and 60 (with various exemptions) to keep a longbow and regularly practice archery. It was repealed in 1960 by the Betting and Gaming Act. Great Britain now has some of the tightest gun control laws in the world. Only police officers, members of the armed forces, or individuals with written permission from the Home Secretary may lawfully own a handgun; in all other cases, handguns are prohibited weapons. Rifles and shotguns require a certificate from the police for ownership, and only after a number of criteria are met, including that the applicant has a good reason to possess the requested weapon. The government has determined that self-defense or a simple wish to possess a weapon is not considered a good reason. Furthermore, secure storage of rifles and shotguns is also a factor when licenses are granted; this has devolved to mandatory overnight storage of a shotgun not in the owner’s home, but at an authorized shooting or hunting club safe.

Nation states also are fairly reluctant to permit their citizens to fight for any group that is not the armed forces. The United Kingdom has laws preventing their nationals from enlisting in foreign armed forces, and they are examining the loss of citizenship for those citizens that join terrorist organizations. Prior to now, the legislation hasn’t been used much; for example, way back in the Greek War of Independence, British volunteers fought with the Greek rebels, which could have been unlawful; it was unclear whether or not the Greek rebels were a “state” per the Foreign Enlistment Act, but the law was clarified, saying that the rebels were a state.

Both the British and American governments turned a blind eye toward their citizens’ participation in the Spanish Civil War in the 1930s. The United States has laws that seem to both make fighting as a mercenary or fighting as part of a non-US entity overseas legal and illegal at the same time. The United States has not banned Americans from fighting with militias against ISIS, although it considers the Turkey-based Kurdish Workers’ Party (PKK), a terrorist organization. The Kurds have turned to the Internet to find foreign fighters, creating a Facebook page called “The Lions of Rojava” with the stated mission of sending “terrorists to hell and save humanity.” The United States has pushed recently for a legally binding United Nations Security Council resolution that would compel all countries in the world to take steps to “prevent and suppress” the flow of their citizens into the arms of groups considered to be terrorist organizations.

This is where the problem may arise. The government of the United States, as well as governments in many European countries, has been extremely reluctant to name militant Islam as an enemy, fearing to antagonize any Muslim that may take offense. Rather than target groups that are true terrorists – calling a spade a spade – it will be tempting to broaden the category to include about any group that is armed and fighting in these conflicts. Should such a broad definition be adopted, it will be the nation states attempt to kill a New Knights Templar in its cradle and could put any volunteer in legal jeopardy. To be continued…