GRAVELEY & WREAKS

IMPORTERS & DEALERS in TABLE & FINE CUTLERY

John Graveley and Charles Wreaks lived and worked in the high rent district of New York City, ordering a variety of elegantly mounted Bowie Knives from the best cutlers of Sheffield, England and selling them to customers in the United States. The New York City Directories for the period show that the firm of Graveley & Wreaks existed for three years, 1836 through 1838, doing business in the Astor House at the intersection of Broadway and Barclay in New York City. With that address and the John Jacob Astor connection they undoubtedly catered to the carriage trade with high end merchandise.

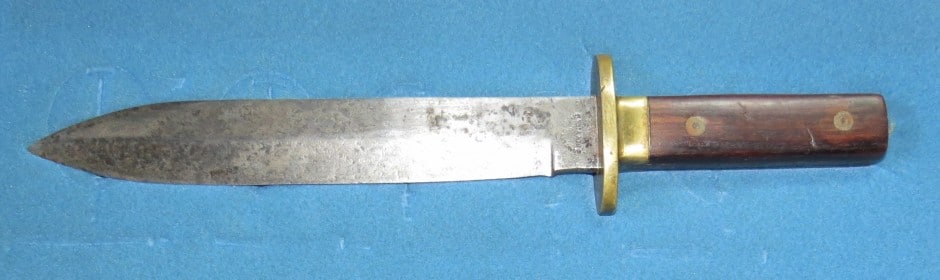

Before we go any further, some readers are going to look at the picture above and say: “That’s not a Bowie Knife.” That is in part because most people who read about Bowies have in their mind’s eye a picture of what this knife should look like, often with a very long blade of the clip point variety (having the appearance of the forward third of the blade “clipped” off) and a cross guard. But back then, many, many knives were called Bowies — clip points (straight or concave), spear points and drop points; even the basic butcher knife was sometimes called a Bowie Knife. Some had cross guards and some didn’t; some were quite fancy; some looked really rough. Handles came in different materials and shapes. One shape was known as a coffin handle — macabrely fitting for a knife that put so many men in one. So for this article, we are using the expansive definition.

The directory reveals the following. In 1833, Charles Wreaks sold goods as a merchant at 82 William Street; in 1834 or 1835 he became an importer at 7 Platt Street. It appears that John Graveley came to New York in April 1836; from 1836 to 1838 he lived at Number 1 Park Place, one street north of Barclay. Wreaks and Graveley established their partnership in 1836; by 1839, however, there was no further mention of the tandem in the New York City Directory.

A John Graveley sailed from Liverpool, England to New York City, arriving on April 1, 1836; his age was listed as 31, so his birth year was about 1805. This may have been his second trip to the U.S. Another man with the same name and birth year arrived in New York City on September 28, 1828. He traveled to England and returned in September 1846.

Additional research indicates that Charles Wreaks was born in Sheffield, England on April 4, 1804, the son of Joseph and Judith Wreaks, and sailed from Liverpool to New York City, arriving on November 19, 1828. Joseph was a merchant and involved manufacturing tools including a cutler’s grinding wheel, saws and later knives. Several of Charles’ siblings also came to the United States; his younger brother Richard died on March 20, 1842 in New Orleans, Louisiana, while his older brother, Henry, passed away in New York City on May 4, 1843. Richard may well have been an agent for the company as earlier he too had resided at 7 Platt Street and his occupation was listed as “agent.” It appears that Charles became a naturalized American citizen on April 9, 1844 in the Superior Court of New York County. The Sheffield Independent reported on April 2, 1867 that Charles Wreaks had died in New York City on March 11, 1867 from “ossification of the heart.”

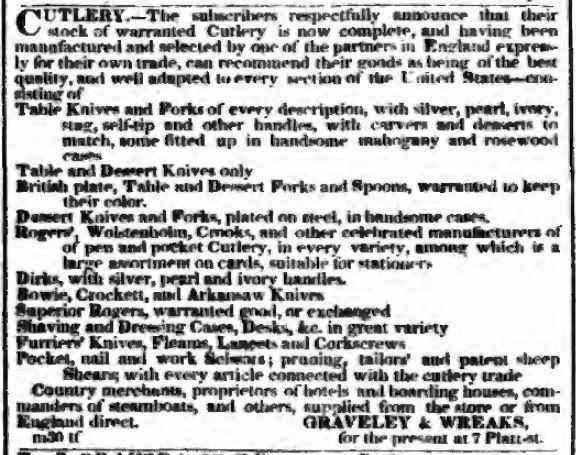

The young men understood the value of good advertising and ran advertisements in the New York Morning Post on April 16, 1836 and May 2, 1836; the New York Morning Courier on May 7, 1836, August 29, 1836 and November 28, 1838. The Graveley & Wreaks advertisement, placed in the New York Herald on May 23, 1836 began with: “NEW CUTLERY ESTABLISHMENT, No. 9 ASTOR HOUSE, NEW YORK.” The presentation left no uncertainty as to the product – “ELEGANT BOWIE & HUNTING KNIVES.” Two months later, another advertisement in the same newspaper expanded the list of products to include “ARKANSAS, TEXAS and HUNTERS knives… butcher, cartouche and scalping knives.”

According to Bill Worthen, Historic Arkansas Museum, when a visitor walked into the Graveley & Wreaks showroom in 1836, he would see a knife marked “Arkansas toothpick” on the blade of a weapon that had no crossguard, sported a coffin-shaped handle. Other knives in the establishment featured other slogans; these were advertised as “Bowie,” “Texas” and “Hunters” knives.

Business became so lucrative that the pair decided to expand their operations outside the northeast – to areas where the Bowie Knife would have an even larger following. In January 1837, the company ran an advertisement in the Nashville Republican in Tennessee, which informed the readers that one partner, now in England, arranged to supply their New York cutlery establishment with an extensive and rare assortment of goods. These goods, the advertisement continued, would arrive in time for the spring trade and included a variety of “HUNTING & BOWIE KNIVES” that could be elegantly mounted in a new style.

The offering included other types of knives, as well as razors, shears and pistols. This partner back in England was undoubtedly Charles Wreaks, as records show that Charles arrived back in New York City from England, on the ship Roscoe, on March 27, 1837 – undoubtedly with the knives in tow. Sensing in even bigger market, the advertisements not only ran in Nashville, but also in Louisville, Cincinnati and Pittsburgh, covering the mighty Ohio River trade route.

Sales appear to have been brisk, but storm clouds were gathering and the gale that followed would lethally flood the company. The demise of the firm was caused by circumstances beyond the two men’s control. The “Bank Panic of 1837” and 1838 caused many businesses to close their doors. However, there was another, more ominous development than pure economics for the weapons’ entrepreneurs. As the popularity of the fighting Bowie knife increased – after the celebrated story of Jim Bowie and his legendary weapon at the Alamo in 1836 – it resulted not only in a marked growth in the number of these weapons, but also the deadly use of the Bowie Knife in murders and duels by the entire spectrum of society – ruffians and gentlemen alike.

By January 1838, caused by an alarmed public and legal furor, even the state of Tennessee – never mistaken as the home of gentility – passed “An Act to Suppress the Sale and Use of Bowie Knives and Arkansas Toothpicks in this State.” Alabama and Mississippi Laws, passed in about the same time, were not as strict as in their northern neighbor, although the laws curtailed the advertising and sales of the Bowie Knife, Arkansas Toothpick and dirks.

The sales of Bowie knives continued in the frontier states of Arkansas, Louisiana and the Republic of Texas, but the bottom fell out of the market. A high-end Bowie Knife valued in double digits in 1837 sometimes sold for only $1.50 in 1838.

Graveley & Wreaks attempted to broaden their stock to compensate in the loss of the Bowie trade. On April 8, 1838 they ran an advertisement in the New York Morning Herald. They mentioned products from prominent English manufacturers Josh. Rodgers & Son, Crooke & Sons and Wostenholm; they mentioned pocket knives and cork screws, cheese scoops and Champagne openers but there was no mention of Bowie knives.

And so, on November 28, 1838 Graveley & Wreaks announced the dissolution of its co-partnership stating “The partnership heretofore existing under the firm of GRAVELEY & WREAKS is this day dissolved by mutual consent.” However, Charles Wreaks added this notice:

“The subscriber (late of the firm of GRAVELEY & WREAKS) will continue the Wholesale Cutlery business as heretofore, and solicits a continuance of the patronage of his old friends. In addition to which he proposes to carry on a commission business for the sale of Sheffield and Birmingham Hardware, and now solicits consignments, flattering himself from his practical experience both in Sheffield and Birmingham Hardware, and a 10 years residence in this city, he can command equal facilities as any house of the trade.”

Charles Wreaks then listed his “Counting House at present” was at No. 14 Gold Street, upstairs. The Sheffield Independent reported similar news on December 29, 1838.

On April 5, 1839, Charles Wreaks placed another advertisement in the New York Morning Courier; this ad offered saws, joiners, hammers, braces and anvils for sale.

Bowie knives stamped Graveley & Wreaks were made in 1835 to 1837. Reading the advertisements indicates that a great variety of older style and newer style knives were offered.

Dr. Jim Batson, an expert on Bowie knives, makes a compelling case that a primary purchaser of Graveley & Wreaks knives was John Jacob Astor, as Charles Wreaks and John Graveley were tenants of Astor in the Astor House. Astor had established the American Fur Company in 1808 and later formed subsidiaries: the Pacific Fur Company and the Southwest Fur Company.

One of Astor’s key contacts in the fur trade was Auguste Pierre Chouteau, a member of the Chouteau fur-trading family, who established trading posts in what is now the state of Oklahoma. A.P. Chouteau was among the first young men to be appointed to West Point by Thomas Jefferson; Chouteau graduated in 1806 with the grade of ensign in the United States Infantry. He briefly served as aide-de-camp on the staff of General James Wilkinson. The following year, A.P. commanded a trading expedition up the Missouri River accompanied by a military unit under Nathaniel Pryor. This Chouteau-Pryor expedition was a direct outgrowth of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

A.P. resigned from the Army in 1807, but served as captain of the territorial militia during the War of 1812. Jim Batson believes that Auguste Pierre Chouteau provided designs for fur-trade knives – to include Bowie knives – to Astor, who gave them to Graveley and Wreaks, who in turn presented them to cutlery firms in Sheffield, England for execution. Given his engineering background from West Point, designing knives would have been well-within the capabilities of A.P. Astor, the “Fur Titan,” is known to have provided August Pierre Chouteau with Indian trade goods at Chouteau’s trading post at the Three Forks of the Arkansas River (Arkansas, Neosho (Grand) and Verdigris Rivers) above Fort Gibson in Oklahoma, transporting the supplies from St. Louis via the Missouri and Osage Rivers and by pack trains and wagons (The fort guarded the American frontier in what became known as Indian Territory beginning in 1824 and when constructed lay farther west than any other military post in the United States, protecting the southwestern border of the Louisiana Purchase.) That relationship with A.P. ended on December 25, 1838, when Auguste Pierre Chouteau died at Fort Gibson.

However, John Jacob Astor had maintained a larger relationship with the Chouteau family. In 1828, where the Missouri and Yellowstone Rivers joined, Astor’s American Fur Company, with help from Pierre Chouteau, Jr. built what became its most famous fur trade post to engage in business with the Northern Plains tribes Assiniboine, Plains Cree, Blackfeet, Plains Chippewa, Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara. Built at the request of the Assiniboine nation, Fort Union Trading Post, then called Fort Union, emerged as the Upper Missouri’s most profitable fur trade post; in 1834, the Pierre Chouteau, Jr. and Company bought all the Missouri River interests of the American Fur Company.

In their short business life together, Graveley and Wreaks featured knives made by several prestigious blade-makers from Sheffield. One specimen has the following marking: “Manufactured by W & S Butcher for Graveley & Wreaks, New York”. Another known marking is a crown over the word “ALPHA” over the words “GRAVELEY & WREAKS” over the words “NEW YORK”. The most frequently encountered marking is simply “GRAVELEY & WREAKS” over the words “NEW YORK”. Sometimes the “GRAVELEY & WREAKS” is shown in an arc (as in this example); sometimes it is flat (horizontal.) Craftsmen stamped these markings into the blade during the forging operation, before heat treating, indicating that many of the knives were custom orders.

The Wreaks family was related to Jonathan Crooke, a well-known blade maker in Sheffield. In 1827 the Jonathan Crookes Company became Jonathan Crookes & Son. One of the advertisements states that the firm imported knives from Crooke, Rogers and Wostenholm knife firms. However, not all knives marked as associated with Graveley & Wreaks were made in England; some were produced here in the United States, although the percentage of U.S. knives offered by the company is unknown. A logical assumption may be that the more elegant a Graveley & Wreaks marked knife is, the more likely it was made in England; therefore perhaps more of the knives produced for the fur trade, where style and appearance took a far back seat to strength and heft, were made in this country.

In addition to clients in the northeast, Tennessee, Ohio, Kentucky and many other states, Graveley & Wreaks appears to have had one more customer – the United States Army. From 1815 to 1832 the Army had no formalized mounted unit and at the start of the great westward expansion that was a intolerable situation. On June 15, 1832 that changed and the service created the United States Mounted Ranger Battalion. The unit served from Illinois to Arkansas, fighting numerous Indian bands to include Comanche and Wichita. Never an efficient force, the unit dissolved one year later, but Congress had already authorized the creation of a mounted regiment and the United States Regiment of Dragoons was formed; the unit would later be renamed the First Regiment of Dragoons. On May 23, 1836 the Congress added the Second Regiment of Dragoons to the Army.

These two regiments immediately began the task of frontier protection – the First Regiment of Dragoons along the southwest border of the frontier in Arkansas, while the Second Regiment of Dragoons soon found itself in the middle of the Seminole War in Florida. As has been the case in many of America’s conflicts the Army found itself somewhat ill-equipped for the character of the fighting required. Thus, among other items of kit, in the late 1830s the U.S. Government issued a requirement for a large fighting knife to be issued to companies of “riflemen” in the Army. The contract, with its specifications of the knife requirements, numbers to be manufactured and the number of sources to produce the knives, has not yet been found in the National Archives. One existing example that was part of the contract came from the Andrew G. Hicks Company of Cleveland, Ohio. This knife, shown in The Bowie Knife: Unshielding an American Legend, by Norm Flayderman (page 174), has the following characteristics: 14 inches overall, with a 9.5-inch slanted spear point, single edge, straight blade; reinforced elliptical brass crossguard; wooden grips. The maker mark is “A. G. HICKS/MAKER/CLEV’D O.”

In 1848 the U.S. Ordnance Department contracted with the Ames Manufacturing Company in Cabotville, Massachusetts for 1,000 knives for a specific “Regiment of Mounted Riflemen.” This was almost certainly the Third Regiment of Dragoons, which had been formed the previous year. An existing example of this buy has an overall length of 12 inches, brass crossguard, wood handle and a maker’s mark on one side and a “U.S.” stamped on the other.

Recently, this study has uncovered a second example of a knife that could have been part of the initial supply of knives to the Army in the late 1830s. Marked “Graveley & Wreaks” and “New York” on one side of the blade just above the crossguard, and “U.S.” on the other side of the blade in the same position, it has the following extremely-similar characteristics of the A.G. Hicks knife: 13.5 inches overall; with a 9.25-inch spear point blade; reinforced elliptical brass crossguard; wooden grips.

This example sold at the Burley Auction Gallery in New Braunfels, Texas on October 25, 2014. In 2015 at the Tulsa Gun & Knife Show, Mr. Floyd Ritter, past-President of the Antique Bowie Knife Association, purchased the knife and subsequently sold it to Mr. Allen Wandling, owner of Midwest Civil War Relics. Nowhere during this chain of ownership was information concerning the knife’s background – other than it was sold by Graveley & Wreaks in the late 1830s – presented.

This study believes that there are three possibilities concerning the early days of this weapon. The first possibility is that Graveley & Wreaks contracted for a U.S. company to make this as part of an unknown quantity of fighting knives to be issued to companies of “riflemen” for the U.S. Army and delivered them as required, after which they were distributed to the First and Second Regiments of Dragoons. The second possible early history of the knife is that it, and an unknown number of other knives like it, were produced for Graveley & Wreaks, sold to John Jacob Astor’s fur trade and delivered to the Chouteau trading post at the Three Forks of the Arkansas River near Fort Gibson. The Chouteaus, seeing they had more knives than they needed and knowing that the First Regiment of Dragoons units at nearby Fort Gibson required knives of this type, resold the knives to the Army at a profit, at which point the Army added the initials “US” on each blade. The third possibility is that the knife was sold by Graveley & Wreaks and many years later came into the possession of the US Government; perhaps the Mexican War, the Civil War or even later.

Graveley & Wreaks marking; the firm sold a wide variety of knives made in the US and England during its short lifespan

Regardless of which option actually occurred, the weapon’s later life remains shrouded in mystery, as do most Bowie knives. Did the dragoon who may have owned it make a career in the Army, fighting in the Mexican War? Did he take his knife with him when he left the service, and if so, where did he go? Could it have served in the Civil War? While we may never know exactly how this knife later lived, we know a great deal about its initial life and how this Bowie and the small firm of Graveley & Wreaks helped shape the US frontier in the early days of our country’s history.