The following slides show a hypothetical framework for operational-level raids against ISIS in Iraq and Syria (although it could also be used in other areas.) I call it Night Stryke. For the last ten years, U.S. Special Operations have been conducting raids against high-value targets, of which the attack against Osama bin Laden in Pakistan was most notable. These attacks, for the most part, were against individuals or small groups of people, perhaps a few dozen at most. Night Stryke envisions attacking ISIS facilities containing perhaps 100 fighters deeper than most of the attacks so far, and as proficiency increases, so would the prospective size of the target and the size of the attacking force that might ultimately be reinforced battalions or tailored brigades.

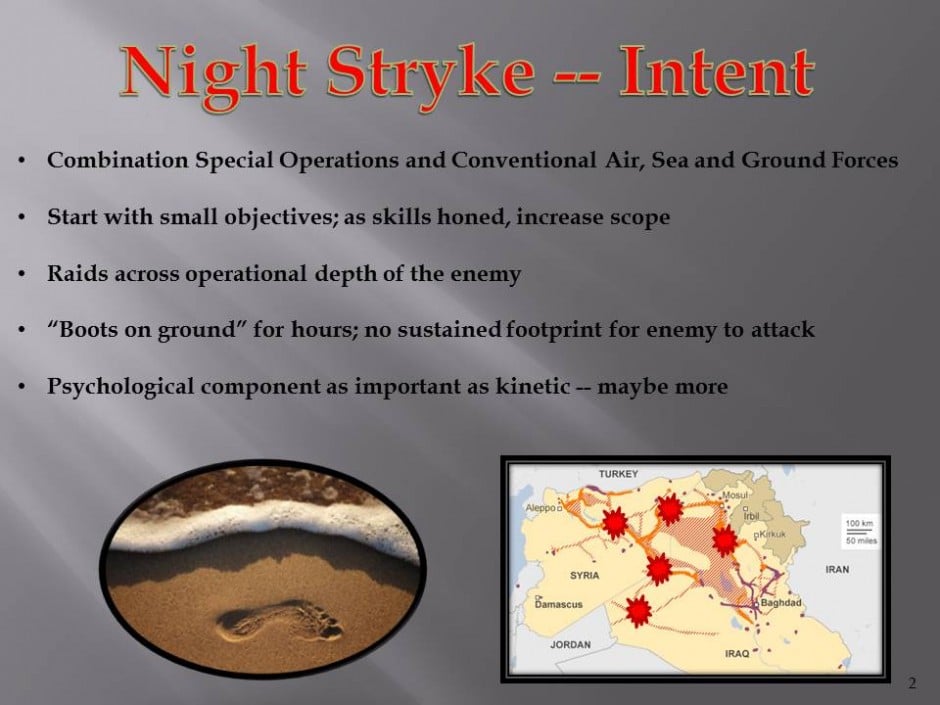

Below are the five facets of the intent of the raids. Because of their scope, both special and conventional forces would be required. Because the transportation is by air, attacks could be launched deep behind the forward progress of ISIS forces. U.S. combatants would be on the ground for only hours (maybe a day at most), leaving no residual footprint to attack. Finally, the ability to strike anywhere at any time would almost certainly add a disturbing psychological burden on ISIS veteran fighters as well as recruits.

The following is the center of gravity (in my opinion) for ISIS forces. Every battle plan must attack an enemy’s center of gravity or else it is wasted effort. You defeat this center of gravity by killing existing fighters and reducing new recruits. There are non-combat strategies, such as turning a majority of Muslims against the militants and encouraging Islam to conduct its own reformation to eliminate it’s warlike tendencies, but those are strategies for the diplomats; this is a strategy for the warriors.

You don’t “take out,” you don’t “degrade,” you kill the enemy in large numbers until you break his will to fight. It has been that way for millennia and despite a recent political penchant to fight bloodless wars, you have to be ruthless or the enemy will be. Additionally, striking the enemy throughout the operational depth of the theater causes the defender to try and defend everywhere, and it is a proven military axiom that he who would attempt to defend every where, adequately defends no where.

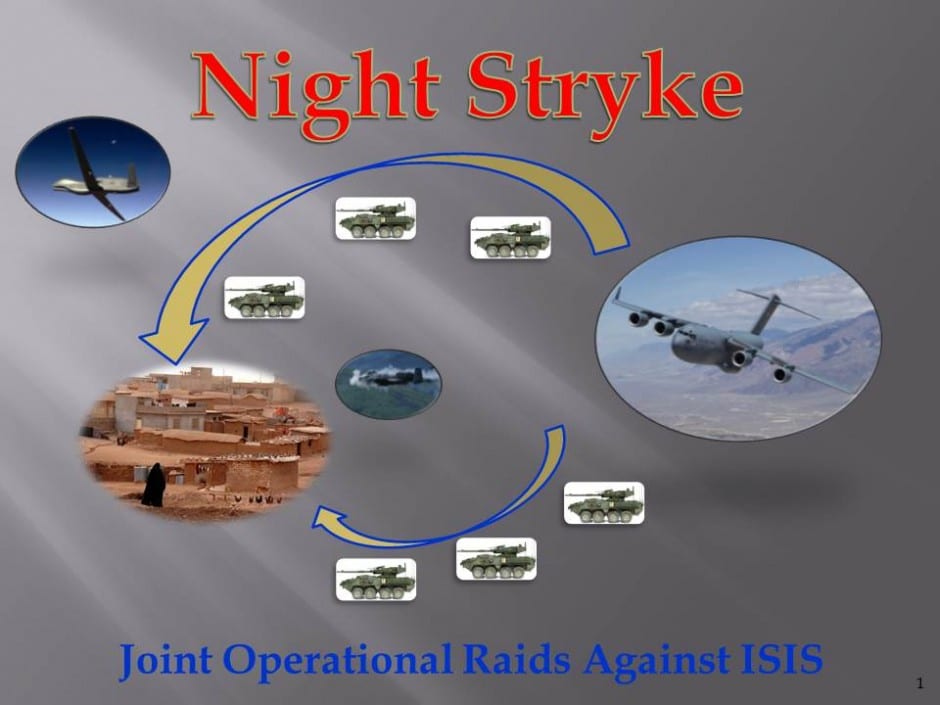

Here is the basic concept. Intelligence assets locate a remote ISIS site occupied by perhaps several dozen up to several hundred jihadist fighters — perhaps a logistical support area for ISIS convoys carrying oil, or an ISIS-controlled oil field. Special operations forces locate and secure a forward operating base that includes terrain on which C-17 airlift aircraft or other platforms can land. As this is 25-75 miles from the target, the ISIS defenders have no idea of an impending attack.

Airlift assets then land combat troops and vehicles, such as Strykers, and this force, perhaps a reinforced battalion, drives to, surrounds and begins to attack the enemy village. Using direct observation, they pinpoint targets for attack aircraft (fixed wing, helicopters, drones, etc.) Air platforms must serve as artillery in this fight because adequate ground artillery simply cannot be transported in enough quantity as they (and their ammunition) take up too much haul space. If the defenders manage a call for help, the same air assets can hammer ISIS columns trying to come to the rescue of their comrades.

Once the ISIS force is eliminated — and the U.S. military simply must change its impotent rules of engagement if it wants to seriously prosecute this war — the force emplaces denial munitions and intelligence sensors to make enemy reoccupation of the facility dangerous. I would argue that the enemy dead should be removed from the target for “proper” burial elsewhere; such a disappearance would further degrade the moral of ISIS fighters who may have signed up to die for their caliphate, but may not have come to terms with disappearing for their caliphate. The ground strike force then rapidly returns to their FOB, boards their aircraft and departs for a secure base hundreds of miles away, perhaps even in another country. Any subsequent media inquiries as to what happened should be met with operational security silence.

How much lift we have available must be balanced against world-wide requirements. Conducting raids to achieve operational gains have been quite successful throughout military history, whether that was Union cavalry raids deep into the Confederacy, or the old Soviet Operational Maneuver Groups that terrorized German rear areas on the Eastern Front in World War II and that kept NATO war planners up at night for forty years in the Cold War. Time to get inside the enemy’s decision cycle, make him defend everywhere. And keep ISIS fighters up at night wondering which of their outposts will be the next one to disappear.

It has already worked at the tactical level and by purely special operations forces. In October 2015, U.S. and Afghan commandos, backed by scores of American airstrikes, attacked an al Qaeda training camp in the southern part of Afghanistan. The assault, which took place over several days, pounded two training areas — destroying elaborate tunnels and fortifications, and killing as many as 200 fighters. Because of the proximity to U.S. bases, C-17s were not needed.

It is time to take it up to the next level in size and scope. It is time to go deep against ISIS and use all special operations and conventional forces at our disposal in even larger raids.