America’s soldiers in World War II come from all corners of America – the teeming cities of the northeast, the rural south, the golden sun of California, the farms of the Midwest, coal country of Appalachia, cold country of Minnesota and even from the Standing Rock Indian Reservation somewhere on the endless Dakota plains. Some are illiterate, needing their buddies to help them read letters from home; others are college boys from schools like “Ole Miss,” University of Maryland, Santa Monica Junior College, University of Kansas, and Bradley Polytechnic Institute.

But college boys are in the minority; most start work at an early age to help the family, and a lot of them are more familiar with hard manual labor than they ever wanted to be. A couple have dangerous jobs up in towering treetops as lumberjacks, or deep underground as coalminers. Several toil on hard-scrabble farms, another is a harbor dredger under the scorching Georgia sun. One stands in front of a hot plate hoping someday to own a small restaurant; another crouches behind home plate chasing his dream of playing catcher in the Major Leagues.

A few are married; a few are spoken for; many think they are God’s gift to women, but more than a few are too shy to even ask a girl to dance. Descended from Austrian, German, Italian, Russian, French, Scottish, Irish, Lithuanian, English, Danish, Canadian, Swiss, Mexican, Korean, Filipino, Swedish, Romanian, Ukrainian, and Polish immigrant parents, they have nicknames like Mac, Hawk, Kenny, Willie, Noodles, Timber, Doc, Vito, Candy, Greek, Buster, Bulldog, Porky and Russian. Not all are born across the fruited plain and are more than happy to tell you about the “old country” of Scotland, Austria, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Mexico, Poland, the Philippines, Greece, China, Norway, Canada…. or Texas.

They all would give their eye teeth to see their mothers just one more time; ladies with names of Pearl, Anne, Fern, Edith, Eva, Pauline, Rose, Tarcila, Grace, Estelle, Antonetta, Ruth, Lupe, Elena, Apie, Ella Fair, Margaret, Maria, Minnie, and Lillie Mae, because every mother thinks that her own son is the cat’s meow. And while each son would trade a few of his tomorrows to be sitting at Mom’s kitchen table tonight, not a one of them one wants to become a Gold Star in her window.

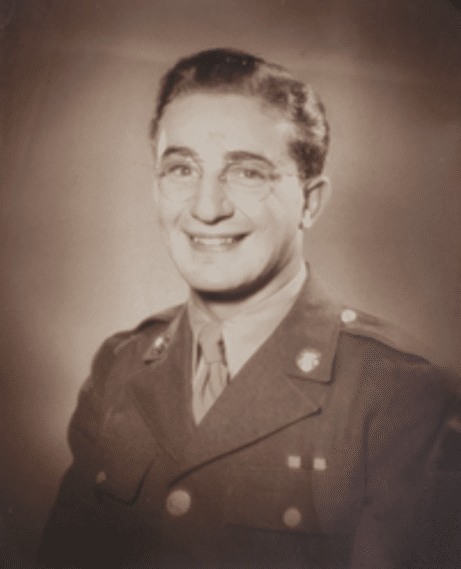

Jay Harvey Lavinsky, at the top of the page, was in Company B, winning two Bronze Stars with V for Valor, before being wounded by six German machine gun bullets outside a small village in Germany on March 4, 1945. However, six days before that, before the dawn’s early light on February 28, something very tragic happened as Company B advances against small arms fire, mines and self-propelled gunfire at the western edge of Berg, two miles southeast of Nideggen. Jay Lavinsky and Harry Nodell, who Jay calls “Brooklyn,” are involved in street-clearing operations. In the dark night, Jay cautiously leads part of the squad, supported by a bazooka team, down the left side of a street, when he hears German drifting from a basement window and tosses a hand grenade through it. On the right side of the street, Nodell spots a German half-track and approaches it, despite a cry of alarm from Lavinsky. The vehicle’s machine gun drops Brooklyn with a lethal burst to the neck. As other soldiers engage the enemy, Jay runs to his fallen comrade and holds him in his arms, screaming: “Listen you son of a bitch; you better not die on me!” Harry looks Jay in the face, winks, smiles, and dies in his arms. Jay will go several days before a change of clothes is available to swap for his blood-soaked uniform – drenched with the blood of his closest friend in the world.

“Brooklyn’ Nodell left a wife and two young daughters behind. Mollie never remarried. He became a Gold Star in his mother Agnes’ window. Jay survived the six bullets and subsequent five operations, and is now 100 years old. He is in a wheel chair and in the last fight of his life, because at least here on this Earth, a person cannot avoid “the Grim Reaper.” The Veteran’s Administration worked miracles and got Jay into long-term care at their West Palm Beach facility, and Jay is taking that fight to the later rounds in boxing terms, because there is no quit in Jay. He knows all about that because when he was young, a family friend in his hometown of Philly is like an uncle to Jay – Barney Lebrowitz, who boxes under the name of “Battling Levinsky,” former light heavyweight champion of the world. Jay learns as much of the “sweet science” as he can from “Uncle Barney” and departs for England on April 5, 1944 to fight for America in some pretty rough places like the Hürtgen Forest, the Battle of the Bulge and the Siegfried Line, where German machine guns are nicknamed “Hitler’s buzz saw” or the chilling-nickname “bone-saw,” one of which got Jay.

So if you live in Florida and see Jay Lavin (his father changed their name after the war,) or see a World War II veteran anywhere you live, reach out and give them a hand — in thanks but also in helping them do the little things in life like walking out to get the newspaper, or even cutting the old-timer’s grass.

Over 400,000 military personnel made the ultimate sacrifice for us in that war. Just don’t just say “thanks for your service”: do something special for them.