Oskar Dirlewanger

Oskar Paul Dirlewanger, SS-Oberführer (SS Senior Colonel), was born on September 26, 1895 in Würzburg. The son of a lawyer, he attended grade school and high school, before passing the Abitur, a test that allowed him to enroll in college. Dirlewanger was never married; he stood six feet tall. He was wounded in combat during in World War I and won the Wound Badge in Black, the Iron Cross Second Class and Iron Cross First Class, as well as the Württemberg Golden Medal for Bravery. In the chaos of post-war Germany, Dirlewanger served on an armored train in a Freikorps (Free Corps) para-military volunteer unit that fought Communist insurgents. He originally joined the Nazi Party in 1922 , with party number 12,517, but he was later expelled from that organization. Dirlewanger then attended the University of Frankfurt, where he obtained a Ph.D. He later re-joined the Nazi Party (party number 1,098,716,) but ran afoul of some local party leaders; the Gauleiter of Württemberg-Hohenzollern, Wilhelm Murr, even attempted to put him in a concentration camp. During the early 1930s, Dirlewanger was a member of SA Brigade 155, but quickly was charged with insubordination and disrespect. A serial sex-offender, Oskar Dirlewanger was convicted of morals’ charges and sentenced to several years in prison (the girl was under 14 while Dirlewanger was 39.)

After his release from prison, Dirlewanger — on the recommendation of his World War I comrade, now SS-Obergruppenführer Gottlob Berger (head of the SS Main Leadership Office) — volunteered to serve with a German military expeditionary force in Spain, known as the Condor Legion; here he helped train Spanish crews in tank warfare, after arriving in Spain in April 1937. His commander, Oberst Ritter von Thoma, of the German Army, rated his performance in Spain as outstanding. For his superior service there, Dirlewanger received the Spanish Campaign Medal, the Spanish Military Service Cross and the Spanish Cross in Silver. Oskar Dirlewanger returned to Germany from Spain in May 1939. In commenting on his past, Dirlewanger said at this point, “Even though I did wrong, I never committed a crime.” After the outbreak of World War II, Dirlewanger wrote to a senior SS officer and volunteered for service as an SS officer, suggesting that a special unit be formed of hunter poachers, with Dirlewanger in command. His rationale was that if men could successfully track and find animals in the forests, those same men could successfully hunt and kill men in those same areas of rough terrain. Promoted to SS-Obersturmbannführer, he was named to command the Special Command Dirlewanger (Sonderkommando Dirlewanger), a Waffen-SS unit (composed of these former prisoners) formed to hunt partisans.

Oskar Dirlewanger and his unit, initially battalion-size, fought partisans in Poland in 1942, guarded Jews in forced labor camps (and the Lublin Jewish Ghetto) and in general made life miserable for Poles in Lublin and Kraków. According to British historian Michael Tregenza, Oskar Dirlewanger and SS-Gruppenführer Odilo Globocnik took part in numerous drunken outings, when Sonderkommando Dirlewanger was assigned to Lublin in 1941 and 1942. The unit transferred to White Russia in 1943, after the SS chief in Poland, SS-Obergruppenführer Friedrich-Wilhelm Krüger, said that the unit was too brutal and corrupt to remain in the General Government. Dirlewanger fought against Soviet partisans through the summer of 1944 in Russia and White Russia, killing thousands of armed – and unarmed – inhabitants in the region. Dirlewanger and his unit took part in the following anti-partisan operations: Operation Adler, Operation Greif, Operation Nordsee, Operation Regatta, Operation Karlsbad, Operation Frieda, Operation Franz, Operation Erntefest I and II, Operation Hornung, Operation Lenz Süd, Operation Lenz Nord, Operation Zauberflöte, Operation Draufgänger I and II, Operation Günther, Operation Kottbus, Operation Frühlingsfest and Operation Hermann.

Heinrich Himmler discussed the unit with his senior SS leaders about this time in the war, and said, “In 1941 I organized a ‘poacher’s regiment’ under Dirlewanger…a good Swabian fellow, wounded ten times, a real character – bit of an oddity, I suppose. I obtained permission from the Führer to collect from every prison in Germany all the poachers who had used firearms and not, of course, traps, in their poaching days — about 2,000 in all. Alas, only 400 of these ‘upstanding and worthy characters’ remain today. I have kept replenishing this regiment with people on SS probation, for in the SS we really have far too strict a system of justice…When these did not suffice, I said to Dirlewanger…’Now, why not look for suitable candidates among the villains, the real criminals, in the concentration camps?’…The atmosphere in the regiment is often somewhat medieval in the use of corporal punishment and so on…if someone pulls a face when asked whether we will win the war or not he will slump down from the table…dead, because the others will have shot him out of hand.”

In August 1944, the Dirlewanger Regiment moved to the Warsaw Uprising (August-September 1944) and the Slovakian Uprising in October-November 1944. During the Warsaw Uprising in Poland, Dirlewanger killed thousands of civilians and his men behaved in such a despicable manner that SS generals at Warsaw begged for the unit to be sent somewhere else. Moving to Slovakia, Dirlewanger and his men ravaged that countryside as well, as they attempted to suppress that uprising. The Dirlewanger Regiment then moved to the Eastern Front in late 1944, first to Hungary; by this time, the unit was receiving drafts of unwilling troopers scoured from the concentration camps.

Sonderkommando Dirlewanger expanded throughout the war and finished as the 36th Waffen-SS Division in Germany, fighting near Halbe as part of the German Ninth Army. German propaganda correspondents and wartime photographers did not follow them in action. This was for good reason, as wherever the Dirlewanger unit operated, corruption and rape formed an every-day part of life and indiscriminate slaughter, beatings and looting were rife. On August 15, 1943, SS-Gruppenführer Curt von Gottberg and SS-Obergruppenführer Erich von dem Bach recommended Dirlewanger for the German Cross in Gold for his achievements against Soviet partisans; he later received the award. He received the Knights Cross of the Iron Cross for his accomplishments in Russia in 1944 and for his role in crushing the Warsaw Uprising. In fighting in both world wars, Dirlewanger was wounded in action at least twelve times. He received the Wound Badge in Black, the Close Combat Bar and the Anti-Partisan Badge.

Dirlewanger avoided death on the Eastern Front, after he was wounded in February 1945, when he turned the division over to Fritz Schmedes. One source says that he came back to command the unit and served with them until about April 12, 1945, when he was wounded once again. Subsequently, Dirlewanger attempted to hide in Upper Swabia at the end of the war. Free French authorities arrested Dirlewanger at the end of May or beginning of June, probably in the Allgäu Alps in southern Germany. Polish laborers, under the employment of the French, identified Oskar Dirlewanger and beat him to death on June 7, 1945 at Altshausen/Upper Swabia, while he was in French captivity, although rumors persisted that Dirlewanger had survived the immediate post-war period and fled to Egypt or Syria in late 1945 to avoid prosecution. French authorities later exhumed the remains of Oskar Dirlewanger from the Altshausen Friedhof on the northwest side of town and confirmed that it was indeed him, although the French file on Oskar Dirlewanger remains locked and inaccessible. After the war, in perhaps the most-classic understatement of the war, Gottlob Berger said this of Oskar Dirlewanger, “Now Dr. Dirlewanger was hardly a good boy. You can’t say that. But he was a good soldier, and he had one big mistake that he didn’t know when to stop drinking.”

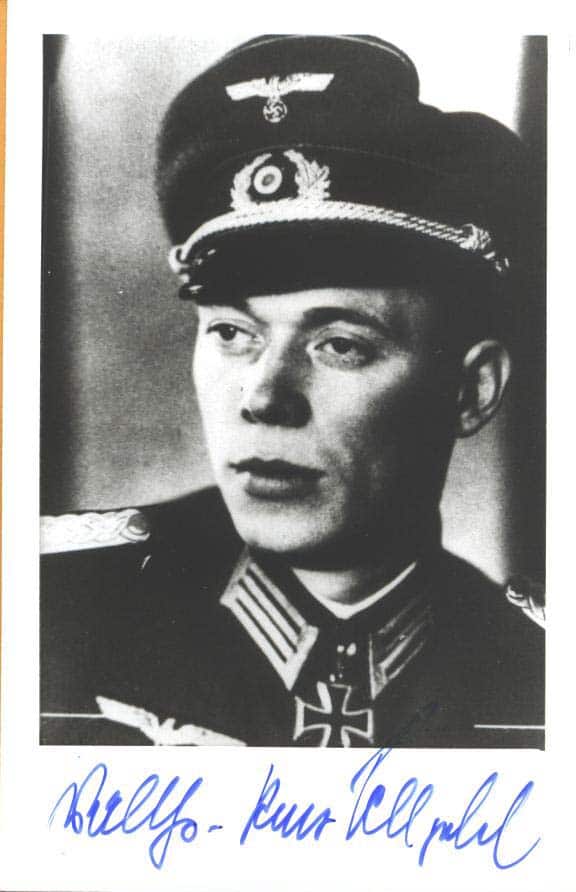

Reputed photo of Oskar Dirlewanger after arrest

Oskar Dirlewanger was undoubtedly a serial sex offender and pathological killer. British historian Michael Tregenza has documented Dirlewanger in Lublin, Poland and presents strong evidence that Dirlewanger murdered Polish women there, to include killing some by Strychnine injections. Had Oskar Dirlewanger survived the aftermath of the war, and been apprehended, the only question would have been which nation would have tried and executed him.

For many years after the war, the operations of Dirlewanger and his unit remained shrouded in mystery. This ended in 1988, when the author found several thousand pages of reports of Sonderkommando Dirlewanger in the U.S. National Archives, later using them to write The Cruel Hunters: SS-Sonderkommando Dirlewanger, Hitler’s Most Notorious Anti-Partisan Unit.

During the war, Dirlewanger’s unit had the following designations:

Wilddiebkommando Oranienburg (June 1940 to July 1940)

Sonderkommando Dr. Dirlewnager (July 1940 to September 1940)

SS-Sonderbataillon Dirlewanger (September 1940 to September 1943)

Einsatz-Bataillon Dirlewanger (numberous occasions in 1943 and 1944)

SS-Regiment Dirlewanger (September 1943 to December 1944)

SS-Sturmbrigade Dirlewanger (December 1944 to February 1945)

36. Waffen-Grenadier Division der SS (February 1945 to May 1945)